Contrasting Platforms in Peru's Presidential Runoff

Contrasting Platforms in Peru's Presidential Runoff

Given the polarized race, this bicentennial election will be anything but a celebration. AS/COA Online previews the platforms of Pedro Castillo and Keiko Fujimori.

Peru’s 2021 elections were meant to be a celebration: the next president will be sworn in on July 28, which this year will mark the country’s bicentennial. After five tumultuous years, the country was cautiously looking forward to a new era.

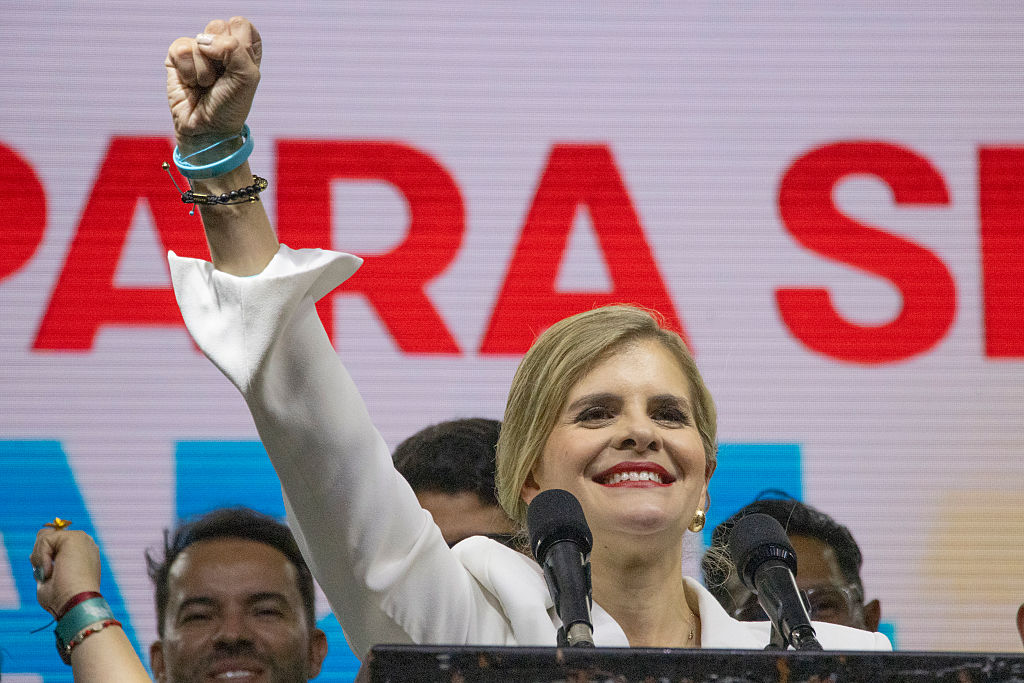

Those hopes came crashing down on April 11, when two of the most polarizing candidates—leftist political novice Pedro Castillo and right-wing political heiress Keiko Fujimori—came out on top in the first round to make it into the June 6 runoff. This is first run at the presidency for Castillo, an elementary school teacher and union leader who’s never held elected office, and the third for Fujimori, who, as the daughter of disgraced ex-President Alberto Fujimori, became the country’s first lady at age 19 and was later elected to Congress.

While in many races voters say they’re choosing the lesser of two evils, that dynamic has taken on an almost existential dimension in Peru. Swathes of voters fear both Castillo’s socialist rhetoric and his too-close-for-comfort proximity to the Marxist Shining Path guerrillas, as well as the ruthless and authoritarian tendencies of Fujimori and criminal administration of her father. That said, what might deter some voters is what draws others. Many of Castillo’s supporters are drawn to him precisely because he comes from outside the Lima-based political establishment. Fujimori’s supporters, meanwhile, see her as a known quantity who will be more likely to maintain some sort of status quo, albeit one that is far from stable.

The uncertainty has sent the Peruvian sol on a rollercoaster during the campaign, and the currency hit a new historic low against the U.S. dollar on May 26.

In 2021, ten countries in Latin America hold elections—five of them presidential contests—while reeling from the pandemic's devastating impact.

See how the race between Pedro Castillo and Keiko Fujimori is shaping up ahead of the June 6 vote.

A vast, ancient gap in living standards helps explain the presidential frontrunner’s appeal.