Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico

Explainer: U.S. Immigration Deals with Northern Triangle Countries and Mexico

The Trump administration seeks to stem migration through a bevy of new pacts with Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico.

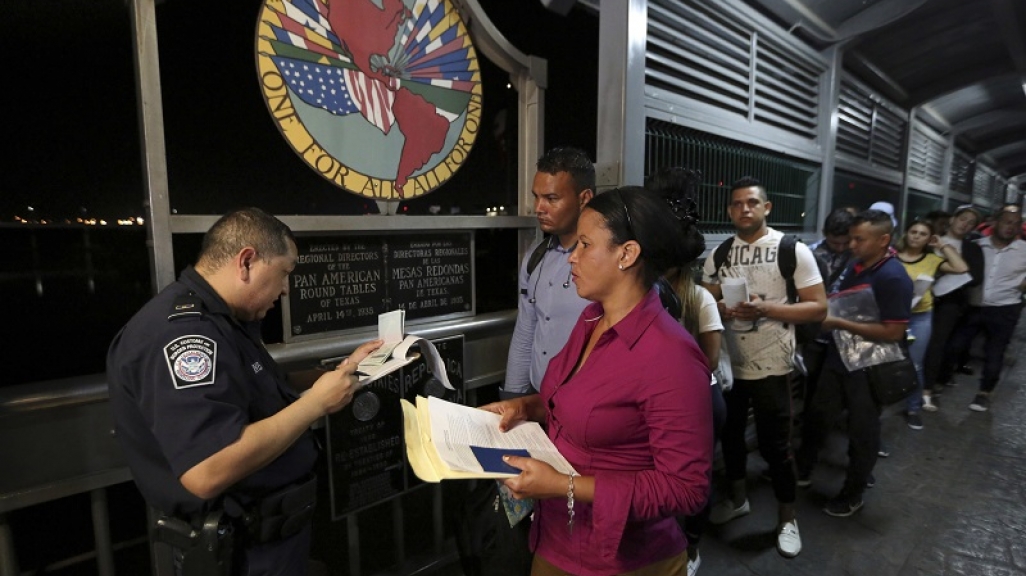

It’s no secret that under U.S. President Donald Trump’s watch Washington has adopted a strict immigration policy: slashing the country’s refugee cap, prohibiting migrants who pass through another country from seeking asylum in the United States, and bolstering immigration policing. The approach puts the Northern Triangle countries—Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—along with Mexico in the crosshairs. Taken together, these countries account for the top four nationalities apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border. One way the Trump administration is seeking to restrict Central American migration is through bilateral agreements with each.

AS/COA Online takes a look at how these agreements came about, what is known so far, and the possible implications of sealing off the Northern Triangle.

Mexico

On May 31, Trump threatened to slap escalating tariffs on Mexican goods if the country did not significantly curb Central American migration through its territory. By June 7 the two countries reached an agreement that gave Mexico a 90-day deadline to show progress on stemming the flow.

Under the signed deal, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, agreed to deploy National Guard troops throughout Mexico with a focus on its southern border, as well as dismantle human smuggling and trafficking organizations. AMLO started by deploying 6,000 National Guard troops to Mexico’s southern border in June. At the beginning of September, Mexico’s Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard said the AMLO government had deployed more than 25,000 National Guard personnel to both its southern and northern borders and pointed to U.S. government figures showing a 56 percent decrease in border apprehensions between June and August as a sign of success. Per his own government’s figures, Mexico deported a total of 83,830 migrants during the first seven months of 2019, a 31-percent increase from the same time period in 2018. Some 96 percent of the 2019 deportees were from the Northern Triangle.

In a late September meeting, U.S. officials recognized Mexico’s efforts but pressed for a U.S.-Mexico safe third country agreement, which the Mexican government declined. A safe third country agreement is an accord between two countries in which migrants must seek asylum in the first country they cross, making them ineligible for asylum in the second country unless the initial request was denied.

The pact also expanded Migration Protection Protocols (MPP), dubbed the Remain in Mexico program, to allow the United States to deport asylum seekers to cities along Mexico’s northern border while waiting for their cases to be processed. That meant asylum seekers sent back to Tamaulipas, a state the U.S. State Department warns Americans not to visit due to violence and human trafficking. Since MPP’s implementation in January, the White House says at least 42,000 migrants were sent to Mexico. Meanwhile, asylum requests have spiked in Mexico, totaling 23,700 between June and August this year—a 276 percent increase over the same period in 2018.

Mexico also pledged to work with El Salvador and Honduras to curb emigration from those countries. AMLO agreed to expand tree-planting initiatives across the two Central American countries with the goal of creating jobs and economic opportunities in the region.

Guatemala

After months of negotiations and a July 23 tariff threat, Trump and outgoing President Jimmy Morales reached an immigration deal on July 26 that functions much like a safe third country agreement, though the text does not use that wording. The agreement on Cooperation Regarding the Examination of Protection Claims, makes migrants heading north through Guatemala ineligible for asylum in the United States, requiring them instead to request protections in Guatemala. Those who do try to seek asylum in the United States would be deported to Guatemala, though logistics regarding deportations and funding remain unclear. Salvadoran and Honduran migrants would be particularly affected.

Should the agreement get implemented, critics have questioned Guatemala’s ability to process the resulting asylum requests. Guatemala’s national asylum office has four employees and received a total of 257 asylum petitions in 2018, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Given that over 100,000 Salvadoran and Honduran migrants were apprehended at the U.S. border in 2018, Guatemala’s asylum system would experience a significant increase in applications.

Prior to the deal’s signing, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court issued three injunctions blocking Morales from declaring Guatemala a safe third country and signing an agreement without the approval of Congress. The court later overturned its injunctions with a September 10 ruling that upheld the agreement and allowed the government of Guatemala to continue its immigration negotiations with the United States. The ruling also notably sustained that the agreement must be ratified by Guatemala’s Congress before going into effect. As it stands, the deal has not yet been approved by Congress, and 82 percent of Guatemalans oppose it, according to a Prensa Libre poll published in August.

Adding to the uncertainty is the fact that Alejandro Giammattei, who has openly criticized the deal since the campaign trail, will be sworn in as president on January 14, 2020. Giammettei expressed that Guatemala is not in a position to process and protect asylum seekers, given the country’s own problems with insecurity. Despite his early criticism, the president-elect seeks to negotiate aspects of the deal with the Morales administration and US officials. In an August meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Giammattei asked for the safe third country label to be taken off the table and be replaced with an official statement outlining that the deal only requires Salvadoran and Honduran migrants to seek asylum in Guatemala.

Guatemala’s homicide rate has been decreasing since 2009. Still, InSight Crime reported a rate of 22.4 murders per 100,000 people in 2018. This insecurity contributes to emigration; nearly 17,000 Guatemalans were apprehended at the U.S. southern border in 2018, making it the largest group arriving there from the Northern Triangle.

El Salvador

Nayib Bukele has prioritized improving bilateral relations with the United States. Over a series of meetings in July and August, the new president and U.S. officials discussed ways to combat crime and gang activity, reduce Salvadoran emigration to the United States, and promote U.S. investment in El Salvador. On August 28, the two countries signed a letter of intent to work together on these issues.

On September 20, Bukele and Trump’s efforts culminated in a signed immigration agreement deal similar to the one Guatemala agreed to months before. While Washington characterized it as a cooperative asylum agreement, the deal would also function like a safe third country agreement. If implemented, it would require migrants to seek asylum in El Salvador if they pass through the country en route to the United States. Details of how and when it will be implemented remain unclear. After the agreement’s signing, El Salvador’s Foreign Minister Alexandra Hill Tinoco stated her country and Washington still need to hammer out details such as how to improve border security and asylum procedures in both countries as well as determine potential aid from the United States.

The agreement also includes a solution for the 200,000 Salvadorans in the United States under temporary protection status (TPS), whose protections will expire in January, though those details also remain unclear. Trump has tried to end TPS for Salvadorans and other groups, but U.S. courts have thus far blocked his efforts.

Though El Salvador had an alarming 103 homicides per 100,000 people in 2015, the rate dropped roughly 50 percent between 2015 and 2018. Days after inking the immigration deal, the U.S. State Department lowered its travel warning to a Level 2, recommending that travelers “exercise increased caution when traveling to El Salvador due to crime.” The previous Level 3 warning urged travelers to reconsider visiting the country at all.

In 2018, 46,800 Salvadorans requested asylum worldwide, making El Salvador sixth in the world for new asylum applications. The country received 20 asylum requests the same year, according to the UNHCR.

Honduras

Honduras and the United States signed an asylum cooperative agreement on September 25. Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, named a co-conspirator in a U.S. drug case involving his brother, and the Trump administration came to an agreement weeks after Honduran Foreign Minister Lisandro Rosales insisted that the country was not considering a safe third country agreement. Similar to the Guatemala and El Salvador deals, the U.S.-Honduras pact does not mention the safe third country designation. Yet, this accord would also allow the United States to deport migrants who arrive at the U.S. border after having crossed through Honduras. Those migrants would then be required to seek asylum in Honduras before they can request protections in the United States. The deal does not yet have an implementation plan, and the official text of the deal has not been made public. Journalist Hamed Aleaziz of BuzzFeed News obtained a copy and reported that the text states that the agreement will not go into effect until both countries have completed the “necessary domestic legal procedures” and establish an implementation plan. Aleaziz also reports that the text says the United States will be responsible for the transfer of asylum seekers to Honduras, while the who and how many migrants will be transferred back to Honduras remains to be decided.

On September 27, the countries signed two additional agreements to boost bilateral relations. They agreed to strengthen immigration enforcement and asylum capacity in Honduras, collaborate on criminal investigations into gangs and human trafficking networks, and expand information sharing.

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security press release, once the agreement is implemented, it will also serve to boost Honduras’ asylum capacities. About 100 people sought asylum in Honduras, according to the UNHCR. In the same year, 77,128 Hondurans were apprehended at the U.S. border.

Podcast: Making Sense of a New U.S.-Mexican Migration Deal

Podcast: Making Sense of a New U.S.-Mexican Migration Deal Update: El Salvador's Nayib Bukele Marks 100 Days in Office

Update: El Salvador's Nayib Bukele Marks 100 Days in Office