Explainer: Guatemala's Presidential Election

Explainer: Guatemala's Presidential Election

With the first-round vote slated for June 16, here’s a look at what’s at stake and who’s still in the running.

Updated, June 13 — Guatemala will have its first round of presidential elections on June 16. Over 20 candidates declared their intentions to participate in the race. But, a month before the vote, the Constitutional Court ruled on the legality of four candidacies, including the top three names in polls: Thelma Aldana, Zury Ríos, and Sandra Torres. The court disqualified the first two.

AS/COA Online takes a look at what’s at stake in this election.

Election basics

Guatemala’s 8.1 million eligible voters will head to polls to choose 340 mayors, all 160 seats in Congress, and a president. If no presidential candidate receives more than 50 percent of votes on June 16, a runoff is scheduled for August 11. The winner will take office on January 14 next year. Presidents can only serve one term.

Voting is not obligatory, but Guatemalans do turn out to vote in relatively high numbers. In 2015 69.7 percent of eligible voters cast ballots, and in 2011 that number was 69.4 percent. This year, eligible citizens living abroad in the United States will be able to vote for the first time, with some 6,000 expected to cast ballots.

The corruption conundrum

A corruption scandal clouded Guatemala’s last presidential elections, and it continues to cast a long shadow. In 2015, then-President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti resigned over their involvement in a corruption ring known as La Línea. In fact, it was Aldana, attorney general at the time, in partnership with the UN agency known as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), who investigated the scandal leading to the resignation and subsequent arrest of the disgraced president just days before the first-round vote.

In that context, President Jimmy Morales, a comedian and first-time candidate, ran as an outsider, promising to curb corruption and support the CICIG’s efforts. In January 2017, when two of Morales’ family members were arrested by crimes investigated by the CICIG, the president said on Twitter that, “The rule of law must prevail over all.” Seven months later, however, Morales would declare the Colombian CICIG Commissioner Iván Velásquez persona non grata days after the agency and Aldana accused the president of illegal campaign financing.

Since then, the presidency’s attacks on the CICIG have escalated. In December 2018, Morales threatened to expel its members from Guatemala but was blocked by the Constitutional Court. Morales also said he would not renew the commission’s mandate, which is set to expire in September 2019.

As the country heads into the next election, more than a fifth of legislators are under investigation for corruption, and 92 percent of the population does not trust Congress. On the other hand, voters do appear to have faith in the CICIG: 72 percent think the agency should remain in Guatemala.

If Morales does not extend the CICIG’s mandate, the commission may well not exist by the time the next president takes office. Frontrunner Torres said in a May 31 interview that the CICIG became politicized when Aldana decided to run, “casting doubt on the credibility of what they were doing.”

During a presidential debate on June 2 that Torres did not attend, National Progressive Party (PAN) candidate Roberto Arzú, Let’s Go’s Alejandro Giammattei, and Humanist Party candidate Edmond Mulet commented on the CICIG. Arzú argued the CICIG should not continue, saying, “Justice must be from Guatemalans, for Guatemalans, by Guatemalans.” Mulet proposed a “perfected CICIG” and stressed the importance of international help in the fight against corruption. Giammattei said he would focus on a national solution and argued that a CICIG-dependent attorney general’s office is not one.

Who’s out?

During the week of May 13, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court barred four candidates from running for different legal reasons.

Aldana was disqualified on May 15 over technicalities involving what’s known as a finiquito, which certifies candidates’ ability to run by ensuring they had no convictions or conflicts of interest during time as public officials. Aldana is accused of a fraudulent hire she made as attorney general. The criminal case against her has not been decided, and Aldana says it is politically motivated because her anti-graft record served as a threat. The Seed Movement candidate has been in El Salvador since March, when an arrest warrant was issued for her.

In early June, a document—issued on May 17 in which a judge requested a “red alert” for Aldana’s extradition—started to circulate on social media and made headlines. The request, addressed to the Interpol division in Guatemala, was based on the same fraudulent hire accusation that motivated the previous arrest warrant. In an interview with Univision, Aldana said the accusations are false, and that she would not return to Guatemala because her security was not guaranteed there.

More controversy rose on June 3, when a new accusation was presented by Guatemala’s Interior Minister Enrique Degenhart. The minister said Aldana traveled to the United States on May 15 with an official passport that she is no longer authorized to use. During an interview with CNN the same day, Aldana said she used a regular passport and showed that the last stamp on her official passport dated back to April 2018.

On May 14, the court also rejected Ríos’ candidacy. The ruling was based on the Article 186 of the country’s Constitution, which prohibits relatives of heads of coups d’état from running for the presidency or vice presidency. Ríos is the daughter of late dictator Efraín Ríos Montt. After the court’s ruling, Ríos appealed to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and presented a copy of the complaint to the Organization of American States. She argues that the rejection of her candidacy is a violation of her rights to vote and be elected, as guaranteed by the Constitution.

Mauricio Radford, presidential candidate of the Strength party, is accused of abuse of authority during his time running the national registry. On May 15, the court disqualified him. Mario Estrada, another candidate out of the race, who was making his fourth presidential bid, was arrested in Miami in April for ties to Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel.

Who’s in?

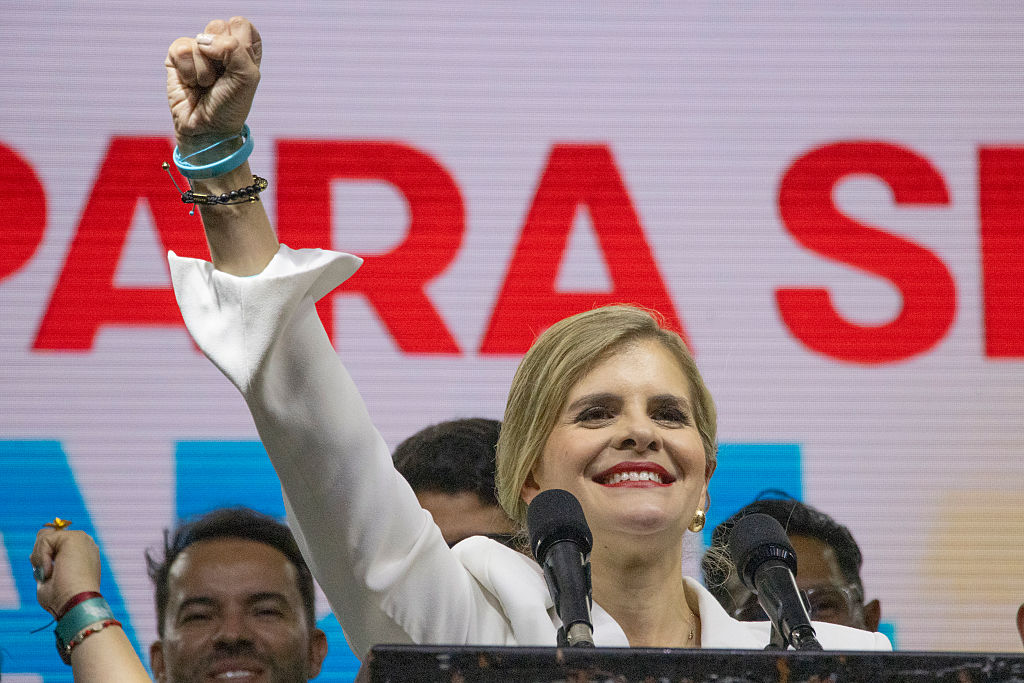

Out of the candidacies considered by the Constitutional Court, only National Unity of Hope (UNE) party candidate Torres remained in the race, with a provisional protection.

In February, the attorney general’s office accused the former first lady of illicit financing during her presidential campaign in 2015 and requested that she be prosecuted and her immunity as a candidate revoked. After the Supreme Court denied the request, the attorney general submitted it to the Constitutional Court to override the decision. On May 17, the Constitutional Court upheld Torres’ immunity through a provisional ruling. The court does not have a deadline to issue a final decision, and it remains unclear if there will be one before election day.

Torres is the most well-known candidate but also has the highest rejection rates. According to an April Pro Datos survey, 49 percent of voters say they would never cast a ballot for her. Her supporters are mainly in rural areas and among voters with low socioeconomic status.

The candidates who rank next in the polls are Giammattei, Arzú, and Mulet.

Giammattei is on the presidential ballot for the fourth time. He is associated with extrajudicial deaths that occurred during his time as penitentiary system director but for which he was exonerated.

Arzú is the son of former President Álvaro Arzú, whom Morales nominated as an ambassador to promote commerce between Guatemala and South America. In March, a judge in Miami ordered his arrest for failing to appear before court after not paying an outstanding debt for consultancy services to the firm of Latin American political consultant J.J. Rendón. Arzú claims it is a civil case that should not jeopardize the legality of his candidacy. Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal has not ruled on this case.

Mulet has been out of Guatemala for much of the last two decades as a diplomat and at the UN, where he was assistant secretary-general for peacekeeping operations. Mulet has been tied to a scandal involving illegal adoptions in Guatemala in the 1980s but says the charges against him are political attacks by the military regime that governed at the time.

Editor’s note: This article originally said Guatemalans were electing 158 legislators to Congress, which was the previous size of the legislature. That said, a 2016 reform added two seats and so voters will 160 congresspeople in 2019 elections.