Explainer: B3W vs BRI in Latin America

Explainer: B3W vs BRI in Latin America

Washington’s Build Back Better World Initiative—still taking shape—seeks to offer an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

In June 2021, G7 partners announced the Build Back Better World Initiative, or B3W, which will provide an alternative for countries worldwide to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, known as the BRI, for infrastructure development. Latin America is the first region on the B3W’s radar. To that end, in September, U.S. officials completed a listening tour to Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama, with visits on deck to other regions before the initiative’s formal launch—expected to come in 2022.

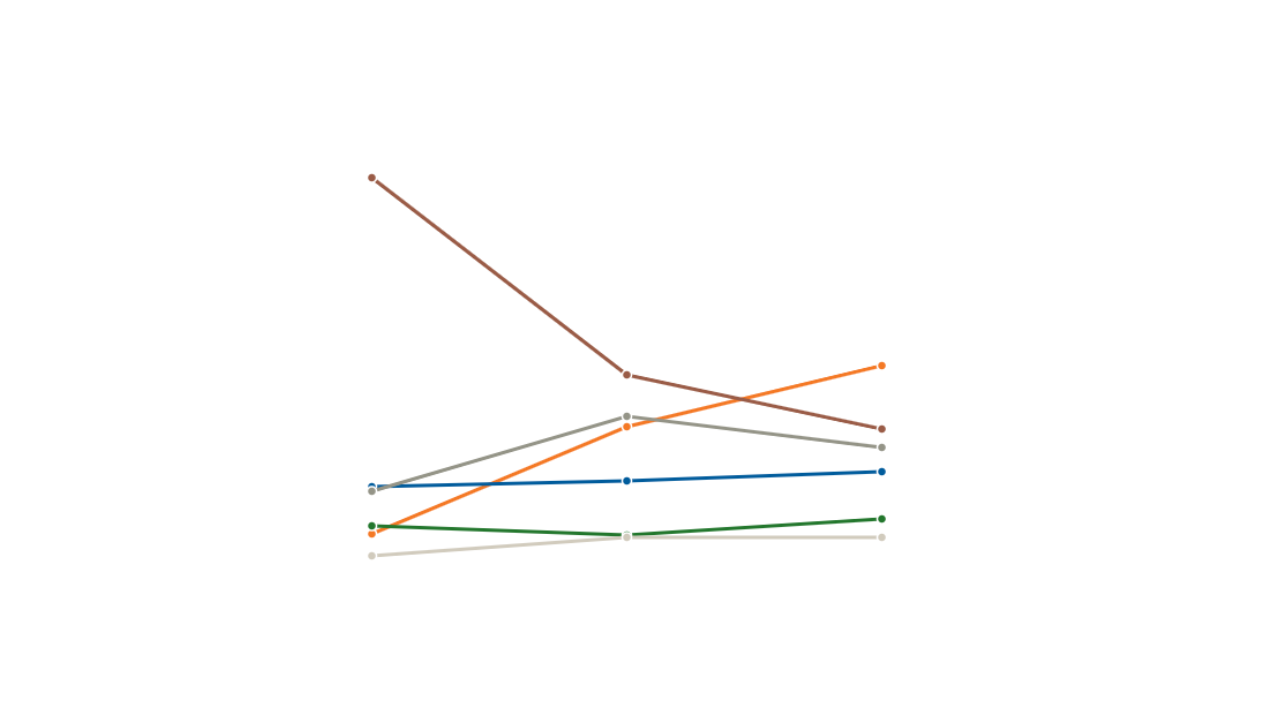

The B3W is young in development, but, as the name reflects, it can be viewed as an international extension of the White House’s domestic Build Back Better project while providing an opposing option to Beijing’s global infrastructure goals. In 2000, Washington was the principal trade partner for every country in South America except for Paraguay. But, two decades later, China displaced it for the top spot in all South American countries except Ecuador and Suriname and is close on the United States’ heels in Colombia.

The rise of China’s economic influence in the region dates back before the BRI, with loan awards amounting to over $137 billion since 2005 from some of its top lenders—China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. (Despite this expansion, in 2020 neither bank provided new loans, but merger and acquisition deals from Beijing still increased, particularly in electricity infrastructure.) This dynamic shift is also marked by China’s recent application to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, the trade pact that replaced the Trans-Pacific Partnership that the United States abandoned under the Trump administration.

Washington and allies say the B3W would offer a transparent alternative with anticorruption safeguards that differ from procedures laid out under the BRI, though details of B3W’s next steps are scant. But, with a U.S. delegation laying the groundwork for the program with this fall’s Latin America tour, AS/COA Online compares B3W aspirations to those of the BRI.

AS/COA hosted a conversation on the evolving bilateral relationship and how it impacts Latin American countries.

China is the top commercial partner for Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, and the U.S. trade dispute is further binding those ties.