Innovation Update: Net Neutrality in Brazil, Mexico, and the Caribbean

Innovation Update: Net Neutrality in Brazil, Mexico, and the Caribbean

As the United States debates net neutrality rules, legislation affecting internet freedoms and mobile app blockages are in the spotlight in Latin America and the Caribbean.

As the United States debates the Federal Communications Commission’s proposed new net neutrality rules, several countries in the Western Hemisphere are also grappling with this issue. Should internet companies or governments interfere with how people use the web, or what users can access? Should authorities be able to gather and save data on web users? These include some of the questions at stake in Latin America and the Caribbean, as Brazil and Mexico pass legislation impacting internet freedoms and numerous Caribbean countries face blockages of popular mobile apps.

Mexico’s Telecom Reform: Addressing Net Neutrality Concerns

On July 14, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto signed into law new legislation that will serve to implement a telecommunications reform approved last year. After months of debate, the so-called secondary law was passed by the Senate and Chamber of Deputies on July 5 and 8, respectively. Though the reform intends to open up Mexico’s telecoms sector to increase competition, the legislation raised concerns about net neutrality and internet freedoms.

Controversy initially arose over language in the bill that put net neutrality in jeopardy and would have created internet fast lanes. Article 146 had originally stated that internet service providers “may make offers according to the needs of the market segments and customers, differentiating between levels of capacity, speed, or quality.” Those in favor of open internet organized street mobilizations and mobilized through social media, with the hashtag #EPNvsInternet trending worldwide in April.

|

Hear an expert view on Mexico's secondary telecom reform laws. |

In response to concerns that this would allow Internet service providers (ISPs) to discriminate among customers and companies based on how much they could pay, the Senate modified the article to favor net neutrality. It now reads that ISPs “must provide internet access that respects capacity, speed, and quality as contracted by the user, independent of the content, origin, destination, end, or application."

The Senate also changed Article 197 after concerns it could allow for government censorship. The language removed originally said that the government could require ISPs to "block, inhibit, or nullify telecommunication signals in events and locations critical to public or national security." Legislators altered the text so that telecom signals may only be blocked in prisons, or when authorities request blockages in order to combat crime. However, the law doesn’t specify who those authorities are, nor the procedure to block the signal.

Concerns remain over other parts of the new law regarding privacy. Telecom providers must provide real-time geolocation information of mobile devices at the request of police during criminal investigations—without a court order. The providers must also keep a record of user data for two years, including the person’s name, communication type, origin and destination of the call or message, data, location, and other personal information. On July 14, a group of 219 civil organizations sent a letter to the Federal Institute for Information Access and Data Protection asserting that articles 189 and 190 violate the right to privacy.

Mobile Freedoms: Blocking Mobile Voice Applications in the Caribbean

The net neutrality debate arose in the Caribbean in recent months after some of the largest regional service providers blocked popular Voiceover Internet Protocol (VoIP) applications. The apps, which include Viber, Nimbuzz, and Tango, allow users to make phone calls and send texts for free using an internet connection and are especially valued by expatriates and those with family living abroad. One provider first began blocking the applications in June in Haiti, home to about 200,000 VoIP users. Since then, providers blocked these apps in Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Blocking VoIP technology means users lose control over which applications they can access. “From what we understand, no other major international provider engages in the practice of blocking legitimate VoIP and similar apps,” wrote Columbus Communications, the Caribbean’s largest wholesale broadband provider, in a statement. In The Trinidad Guardian, several industry experts argue that the continued blocking of applications in Haiti and Jamaica infringe on the rights of customers who purchase internet broadband in order to use the VoIP applications.

|

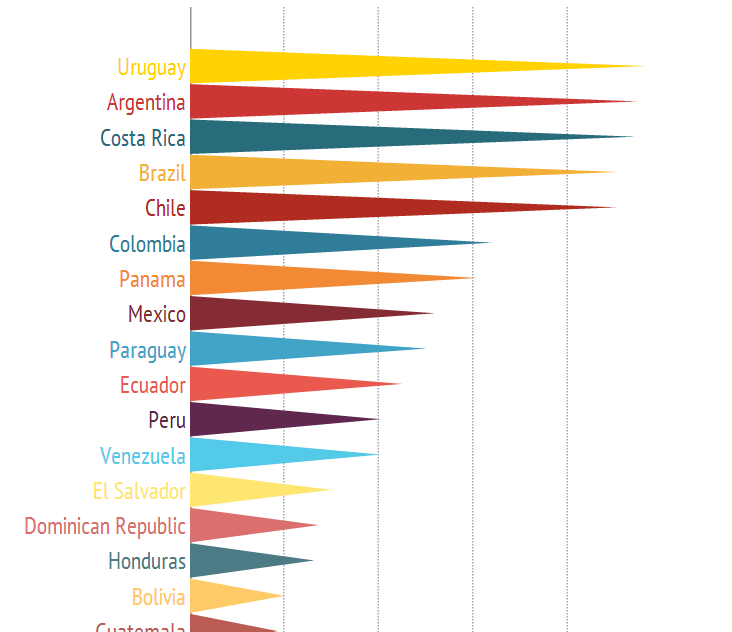

See how countries rank in internet access in a series of infographics. |

The unexpected service change prompted subscribers to express their discontent online, and Trinidad and Tobago’s telecom authority requested to lift the block. Responding to these concerns, the first company to start the blockages agreed to temporarily unblock VoIP apps in Trinidad and Tobago on July 9, and later lifted the block in Haiti on July 16. The provider, however, maintains that the issue is not one of internet freedom. “Unlicensed VoIP operators like Viber and Nimbuzz use telecoms networks to deliver their services, but they do not pay any money for the privilege,” the company said in a press release. “This unauthorized activity puts enormous pressures on bandwidth—which means customers’ data usage experience is negatively impacted as a result.”

Meanwhile, Trinidad and Tobago’s telecom authority plans to investigate the matter, and Haiti’s telecom regulatory commission will monitor the situation.

Brazil’s Net Neutrality Law: On Paper and in Practice

Brazil’s so-called Internet Bill of Rights—approved earlier this year in the wake of the National Security Agency spying scandal—went into effect on June 23. The legislation not only guarantees privacy of online communications, but also establishes net neutrality in the country. While open internet advocates laud the law, uncertainties remain.

First, one central provision about net neutrality has yet to be defined. The law establishes that the president, the independent Brazilian Internet Steering Committee, and the National Telecommunications Agency can make exceptions to net neutrality, such as in the case of national emergencies. This part of the law must be resolved by decree, and a public debate on the issue has yet to take place. Another provision will also require additional regulation: storing user data. The law requires Internet providers to store IP addresses and times users connect for up to one year. Internet companies like Google must store user browsing history for six months.

Even with the majority of the law in effect, there are questions about how it will work in practice. For example, it’s unclear whether service providers can differentiate packages for users that have VoIP apps. In addition, companies that work with data collection for online advertising on social networks will be regulated under the legislation, lawyers say. But if and how these companies ask permission to collect user data remains to be seen. According to the law, companies must erase user data permanently if the user cancels their service. But how online banking and e-commerce companies will handle this rule—given that they deal with sensitive financial data—is in question.