Four Questions Driving Costa Rica's Presidential Race

Four Questions Driving Costa Rica's Presidential Race

Laura Fernández, running to continue President Rodrigo Chaves’ agenda, may win in the first round of a February 1 election marked by insecurity woes.

Updated February 2, 2026—On January 13, just weeks before the country’s February 1 presidential and legislative elections, authorities in Costa Rica announced they had uncovered a plot to assassinate President Rodrigo Chaves. It was a shocking moment that only heightened political tensions in a country experiencing an uncharacteristic rise in violence in recent years.

How to address that violence—and issues like economic inequality—are central to this year’s election, as is Chaves’ high approval. His candidate in the race, Laura Fernández, is polling ahead in a field of 20 candidates with her pitch to continue his agenda.

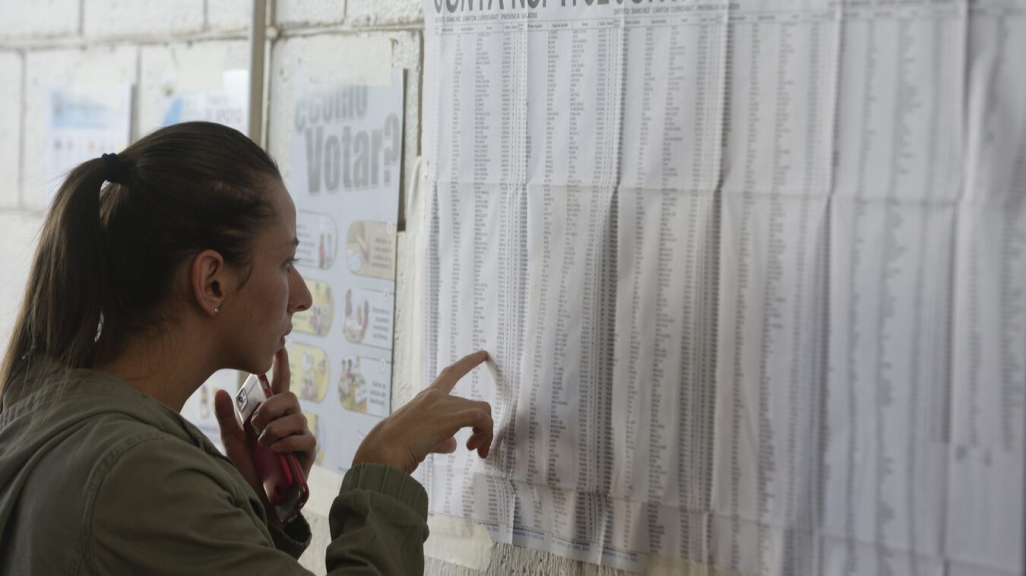

AS/COA Online explores four questions shaping the race for the country’s 3.7 million voters.

AS/COA Online covers major votes across the region for presidents, legislatures, municipal votes, and more.

Laura Fernández, President Rodrigo Chaves’ former chief-of-staff, is polling high enough to potentially avoid a runoff. Ticos vote on February 1.