Environmental Update: Transforming Transportation in Latin American Cities

Environmental Update: Transforming Transportation in Latin American Cities

Cities across the region are implementing innovative transportation projects so their citizens can get from A to B faster—and breathe easier.

More than 100 million residents in Latin America and the Caribbean—about 1 in 6 people—are exposed to unsafe levels of air pollution. That said, the region could get to zero carbon emissions by 2050, says the UN Environment Program. It’d require some big projects to come through (zero deforestation in the region, for one), but the cost of inaction would be greater. The UN says that climate change could cost the Americas $100 billion by 2050, thanks to everything from melting glaciers to a loss in agricultural productivity.

Transportation, which accounted for 27 percent of energy use in the region in 2010, is one of four sectors the report highlights with the greatest opportunity for carbon savings. While investments in renewable energies improve countries’ power grids, a wind farm can’t power a city bus. As such, transportation requires its own set of reforms to become environmentally friendly—and substantive ones if cities are to cut use of gasoline and diesel, which make up 91 percent of fuel in the region. Here’s a rundown of ways Latin American cities are working to renovate their transportation systems for the twenty-first century.

Mexico City: Giving vehicle exhaust a breather

In the 1980s and 1990s, the city suffered from notorious pollution, earning it the nickname of "Makesicko City." But the city implemented dozens of reforms, improving emissions standards and ozone levels.

That said, as the city continued to grow, so did the number of cars on the street. A 2015 court decision put an additional 1.4 million older, more polluting vehicles back on the streets full-time, too. In March this year, ozone levels crossed over 200 on the city’s air quality scale for the first time in more than a decade. The figure represents twice the recommended level, although still stands well below the high of 398 set in 1992.

Beginning in April, Mayor Miguel Ángel Mancera’s administration implemented three months of Hoy No Circula (Today My Car Can’t Circulate), a program that restricts between 20 and 40 percent of cars from the roads each day. The initiative, which hasn’t exactly been embraced by city residents, imposes fines ranging from around $75 to $90, the equivalent of 20 to 24 days’ wages on a minimum salary. Vehicles that run on alternative energies, meanwhile, are exempt.

The city is also considering a measure for tighter emissions standards for heavy-duty vehicles. Black carbon, which comes out of the trucks’ diesel exhaust pipes, is the second-strongest pollutant after carbon dioxide, and the government estimates the regulation could save an estimated 55,000 premature deaths.

Mexico included a unique target to reduce black carbon emissions by 51 percent by 2030 in their Intended Nationally Determined Contribution at the Paris COP21 climate conference. A World Bank study concluded that, if Mexico City could meet World Health Organization emission standards, it could save the city costs equivalent to 2 percent of GDP.

With a look toward infrastructure, officials are also hoping that a new airport—located outside the city limits instead of the current one near downtown—could alleviate city center congestion.

Panama City: Using Japanese technology to expand the Metro

In April, the Central American country inked a $2.6 billion deal with Japan to build a 17-mile-long line for the Panama City monorail. Panamanian officials say the line, Central America’s first monorail and the first in the Americas to use Japanese technology, will be able to carry up to 50,000 commuters from the suburbs to downtown in 45 minutes—a trip that today can take as much as three hours in traffic.

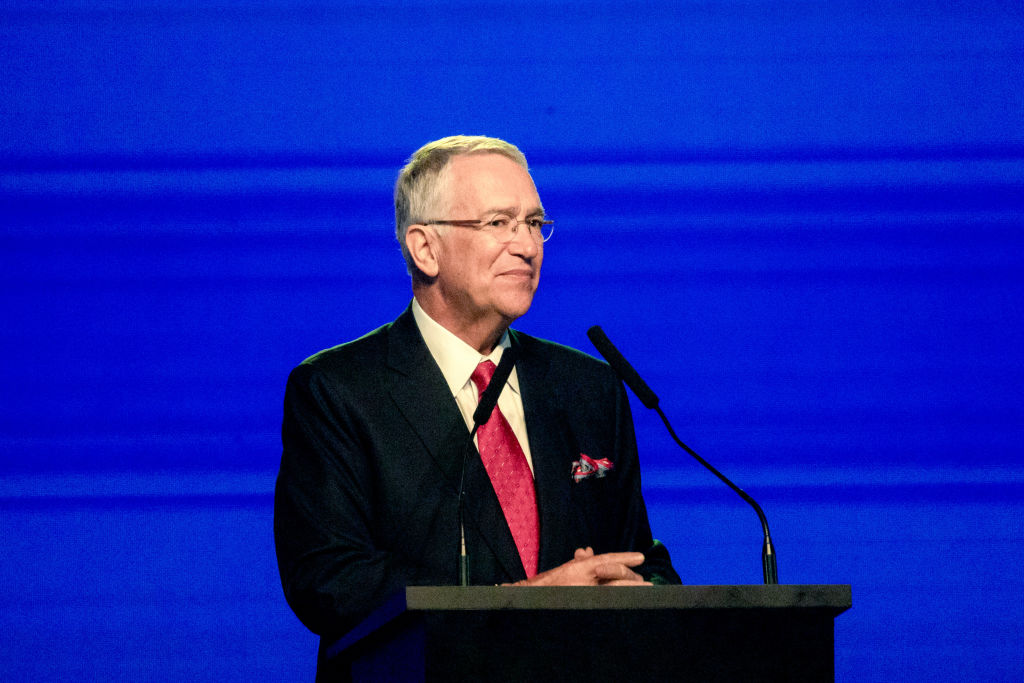

“My administration is committed to make sure that Panama’s economic system becomes a model of sustainable human development for all Panamanians,” said President Juan Carlos Varela at the 46th annual Washington Conference on the Americas, talking about this and other infrastructure projects. “These public investment efforts are being executed with fiscal responsibility.”

Bolivian cities: Converting to natural gas

In 2010, President Evo Morales launched a new agency tasked with converting the country’s vehicle engines to run on natural gas, one of Bolivia’s most plentiful natural resources. The program took off. Within four years, the agency said that almost a quarter of Bolivian vehicles—including 80 percent of public transportation buses, micros, and taxis—had had their engines retrofitted on the government’s dime. While La Paz drivers are reluctant to make the switch, since natural gas doesn’t give the required boost needed to motor up the city’s steep streets, the program has seen significant adoption in Santa Cruz and Cochabamba. The two cities count on 73 and 57 natural gas fill-up stations, respectively, the seventh and eleventh highest tallies in a list of hundreds of Latin America and Caribbean cities. Natural gas makes up 2 percent of fuel use throughout the region.

The benefits are financial as much as environmental. The agency says drivers are now saving more than 50 percent on gasoline bills. The government itself expects to make money on the deal too: while the program is budgeted to cost about $360 million over five years, the country will save an estimated $442 million in petroleum imports due to lowered demand.

Lima: Investing to fight inversion

Nestled between the Andes and the Pacific, Lima is subject to thermal inversion in which a layer of hot air traps cool air—including smoggy contaminants—close to city streets and prevents it from rising and dissipating. The city has one of the highest rates of urban pollution in Latin America, per the World Health Organization, due in part to an old and inefficient bus fleet. A study by the Lima-based Economic and Social Research Consortium found public transport exhaust caused 80 percent of more than 5,100 pollution-related deaths in the capital between 2007 and 2011.

In 2013, the country received funds from the World Bank to create Lima’s first rapid bus corridor, as well as infrastructure for bike paths. Since then, 790 old buses have been destroyed, relieving the city of 26,500 annual tons of greenhouse gas emissions.

Buenos Aires: Prioritizing the pedestrian

Argentina’s capital is living up to its name by working to improve its air quality. Winds coming off the Río de la Plata affect the city’s air quality, but 80 percent of its air pollution comes from vehicle exhaust. Buenos Aires’ environmental protection agency issued citations to 12 percent of vehicles during roadside emissions checks in 2010.

In 2014, under then-Mayor Mauricio Macri, the city won the Sustainable Transport Award after renovating its famed Avenida 9 de Julio corridor. The project replaced some of the 20 car lanes with bus-only ones, adding service for an additional 200,000 daily riders and reducing cross-city travel times by 65 percent. Buenos Aires is in the process of converting 100 city center blocks into pedestrian-friendly paseos, and expanding bike lanes and a public bike share project.