Costa Rica Update: Carlos Alvarado's First 100 Days

Costa Rica Update: Carlos Alvarado's First 100 Days

Issues that defined the presidential campaign remain front and center in the national dialogue.

When Carlos Alvarado, 38, took the reins of the Costa Rican presidency on May 8, he barely got a honeymoon. Instead, hot-button issues that defined the campaign season, such as LGBTQ rights and gay marriage, remain front and center in a heated and public national debate. And though he beat his conservative opponent handily to win the presidency, his rival’s party—the National Restoration Party (PRN)—has set up shop in Congress. The president needs to pass much-needed tax reform, but so far he’s mustered little political capital to do so in an opposition-controlled legislature.

As he marks his first 100 days in office this week, we look at the issues that have demanded his attention.

LGBTQ rights

On August 8, after its longest session in nearly three decades, the Supreme Court ruled that Costa Rica’s ban on gay marriage was unconstitutional and told legislators to rectify the law. If legislators do nothing, the ban will become null and void in 18 months. But Supreme Court justices in Costa Rica are elected by the unicameral Legislative Assembly, and one PRN congresswoman suggested on August 13 that the judges’ places on the bench could be in jeopardy in response to the ruling.

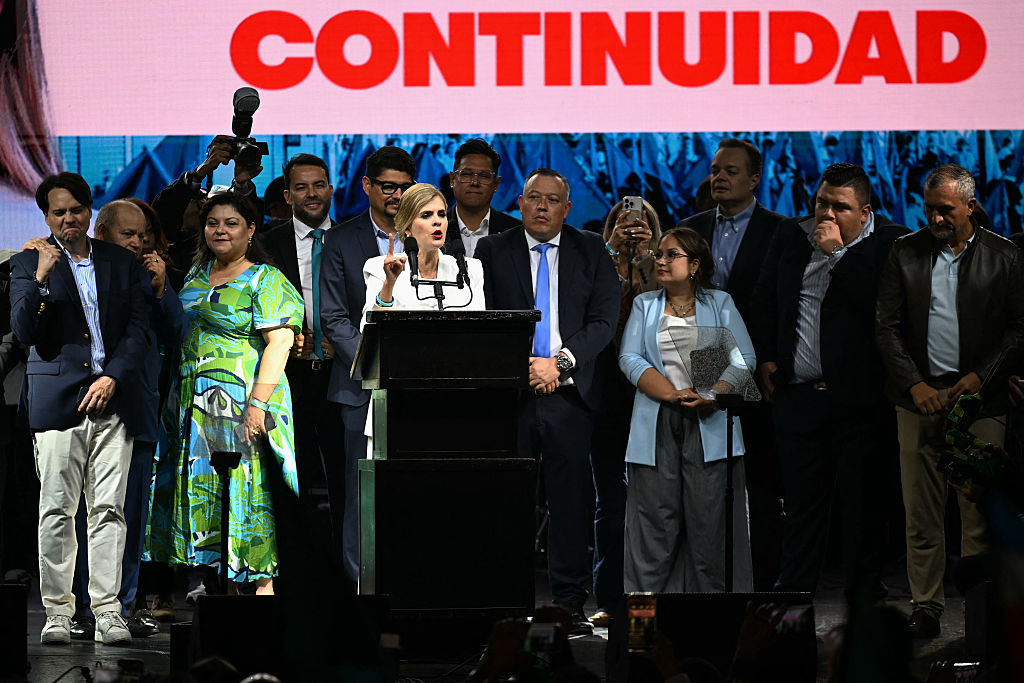

It’s not an idle threat, given that the battle against gay marriage isn’t just part of the PRN’s platform—it’s what propelled them into power in the first place. Back in January, less than one month before the first presidential vote and legislative elections, the San José-based Inter-American Court on Human Rights ruled that member countries must recognize same-sex marriage, a decision two-thirds of ticos opposed. After he promised to withdraw the country from the court, PRN candidate Fabricio Alvarado (no relation) won the first presidential round, and the PRN gained 14 of 57 seats in the Assembly after holding just one in the previous session. The president’s Citizen Action Party (PAC) holds 10 seats, with no alliances strong enough to solidify a majority. While half of the PRN’s 14 reps are evangelical pastors, one of the PAC’s 10 deputies is Costa Rica’s first openly gay official to get elected to Congress.

Gender politics

Trying to focus on tax reform, the president stirred a bee’s nest when in late July he said that it was not the right moment politically to address abortion rights. Abortion is technically allowed if the mother’s life is in danger, but due to a lack of regulation that leaves doctors liable for prosecution if they perform one, the practice is effectively illegal. While campaigning, Alvarado indicated he would seek to close this loophole, thereby clearing the way for abortion in emergency cases.

On July 30, 42 deputies—including two from the PAC—signed onto a bill put forth by PRN Deputy Ivonne Acuña that would define life as beginning at fertilization. The PRN platform calls for abortion to be qualified as murder. Acuña, a PRN vice presidential nominee, has risen to greater political prominence as of late as legislators rallied to support her in the wake of sexist attacks made by a prominent doctor who insulted her intelligence, faith, and appearance.

On August 14, President Alvarado declared confronting violence against women to be a national priority after the murders of two female tourists, one from Spain and the other from Mexico, in two different beach communities one day after the other. The police also announced a $1 million influx to boost security in tourist areas. Tourism represented 6.7 percent of tico GDP in 2017.

Debt and taxes

Passing tax reform has eluded the previous four administrations. Costa Rica has the highest rate of short-term debt among the 15 Latin American countries evaluated by Moody’s, followed by Argentina. The Central Bank projects that if Congress does not pass tax reform, the fiscal deficit could climb from 6.2 to 7.2 percent of GDP and the public debt load from 49.1 to 53.8 percent by the end of 2018, then to 7.5 percent and 58.5 percent, respectively, by the end of 2019. Because of a rule that allows just one deputy to filibuster any piece of legislation, it takes the Costa Rican legislature on average three years to pass one law.

But on August 7, Finance Minister Rocío Aguilar acknowledged that the government made $320 million in payments on internal debt not budgeted for and without legislative approval. The president stood by his finance minister, saying the state “has to pay,” but opposition legislators are keen to put her under investigation.

The charges of mismanagement are sensitive ones after a corruption scandal dominated Costa Rican politics for much of 2017, ensnaring all three branches of government and leading to the early retirement of the head of the Supreme Court in mid-July.