Brazil: Reforms Key to Economic Growth, Prosperity

Brazil: Reforms Key to Economic Growth, Prosperity

Yet again, proving his political resilience, Brazil's Teflon president overwhelmingly bounced back from an unexpectedly close first round to win reelection two Sundays ago. Pushing aside the corruption concerns that dogged his reelection bid earlier in October, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva played into voter fears about state company privatization and social-program cuts to sway 60.8 percent Brazilians. The elections, though, paint a mixed picture for reform prospects during the next four years.

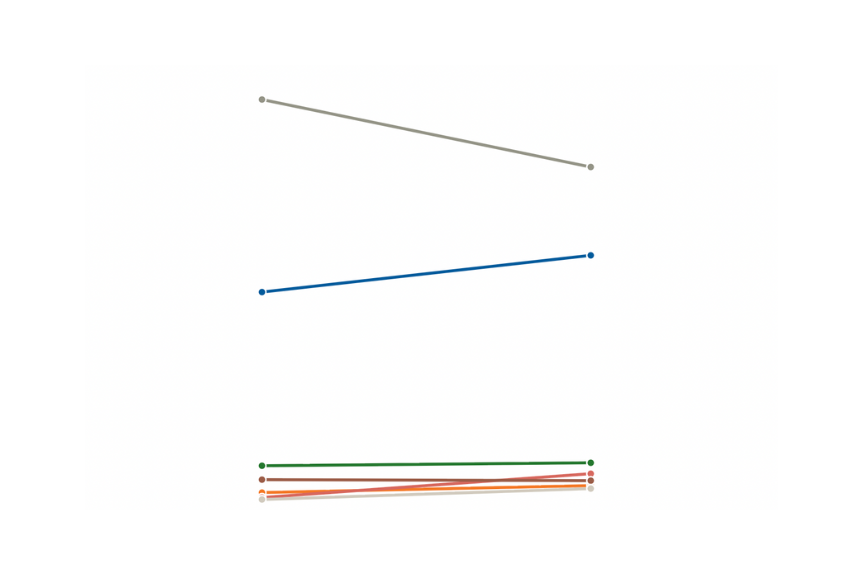

First round results shocked observers and Lula himself. The incumbent fell 1.4 percent short of the margin needed to secure an outright victory, which according to preelectoral polls, looked virtually wrapped up only a few weeks earlier. Responding to a last minute corruption scandal, the latest in a series that have touched the administration, a reenergized electorate expressed its displeasure with a president that had promised to bring ethics and honesty to government.

Four weeks later, the results could not have been any more different. In the second round, Lula coasted to victory nationwide, defeating Mr. Alckmin by 21.7 percent. Not only did he maintain the high first-round support from Brazilians in areas that benefit most from government assistance programs, but scandal fatigue helped to win over voters in the Southeast and West and cut into Alckmin's popularity in the South.

However, while such an unambiguous victory may be good for bringing together an increasingly divided electorate, it casts a dark cloud over reforms key to generating needed economic growth and individual prosperity.

In his four years in office, Lula defied initial market concerns by implementing sound macroeconomic policies that contained inflation and maintained the country's credit rating while augmenting social programs. With the launch of Bolsa Família in 2003, he combined and expanded the schooling, nutrition and cooking-fuel assistance measures of his more conservative predecessor, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, into a larger social safety-net program that doles out cash assistance to roughly 20 percent of the population. His administration has boosted job growth and sent interest rates on a downward trajectory.

But Brazil's long-term fortunes depend on addressing long-overdue reforms and moving beyond a dismal annual growth rate that since Lula took office has hovered below 3 percent.

- Tax reform. It would not only strengthen competitiveness and encourage greater domestic and foreign investment but would also increase employment. In the last 10 years, successive governments have passed minor reforms but have consistently failed to see through sweeping changes. The result is a highly complicated structure of state and federal taxes and a rising tax burden now equivalent to nearly 38 percent of gross domestic product.

- Broad pension reform. A 2003 reform of the system for public sector workers has brought modest fiscal savings and served to reduce the generous retirement benefits for senior civil servants and the judiciary. However, the state-supported program for the private sector remains wildly out of control.

The next government must address politically contentious proposals to increase the retirement age and sever the link between pensions and minimum wage.

Of the various electoral scenarios that would open the door for needed reforms, Lula's second round trouncing of his opponent is perhaps the least likely to motivate action from either the next president or Congress.

Brazilian voters are now left with a country in need of state reforms but a leadership without much incentive to see through their passage. Unfortunately, these are the very reforms critical to Brazil's future. While social-assistance programs are important for immediate relief, the long-term fiscal health of a country depends on fixing the unsustainable policies of today. This is a message that should not be lost on the Brazilian people or their newly reelected president.

Christopher Sabatini is the senior director of policy and Jason Marczak is the policy program officer at the Americas Society and Council of the Americas.