Guide: Venezuela's Political Scenario

Guide: Venezuela's Political Scenario

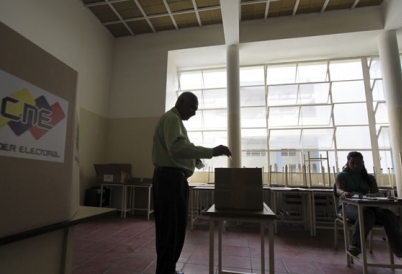

Updated June 9, 2013—On the afternoon of March 5, Venezuelan Vice President Nicolás Maduro announced through national media that President Hugo Chávez died following a battle with cancer. Chávez had remained out of the public eye for three months while undergoing treatment, largely in Cuba. Chávez was due to take office for a fourth term on January 10, but the Supreme Court ruled he could be sworn in at a later time. Following Chávez's death, Venezuela's National Electoral Council (CNE) announced a new election would take place on April 14.

Before heading to Cuba for medical treatment in December, Chávez announced that Maduro would be his hand-picked successor. As vice president, Maduro temporarily assumed the presidency and then ran on the PSUV ticket against opposition candidate Henrique Capriles. On the night of April 14, the CNE announced that with over 99 percent of the votes counted, Maduro won with 50.66 percent. Capriles, who received 49.07 percent of the vote, called for a recount. The CNE agreed to an audit, though Maduro was sworn into office the following day.

What comes next for Venezuela's political future?

Experts Views on Venezuela's Future

The potential for political transition has created uncertainty in Caracas and put Venezuela on the forefront of the hemispheric conversation. President Hugo Chávez's absence from his scheduled presidential inauguration posed questions about the future of the Bolivarian movement, the political, social, and economic stability of the country, and the status of foreign relations under a new Venezuelan leader. Two AS/COA experts weighed in on the impending political transition in Venezuela and what it means for Venezuela's relations with the United States and Latin America.

See expert contributions:

- "The Future of U.S.-Venezuelan Relations" - Eric Farnsworth, Vice President, AS/COA

- "Venezuela's Uncertain Political Transition" - Christopher Sabatini, Senior Director of Policy, AS/COA

"The Future of U.S.-Venezuelan Relations" - Eric Farnsworth, Vice President, AS/COA

AS/COA: Will U.S.-Venezuelan relations improve in a post-Chávez era?

Eric Farnsworth: We would certainly hope that to be the case but much depends on who eventually becomes Venezuela's leader succeeding Chávez. In the near term, relations could actually worsen, as the next president seeks to solidify his political base by claiming the mantle of Chavismo, one of the main tenets being the demonization of the United States. Observers should anticipate additional volatility in the relationship at least for the short term, although certain confidence building measures like the exchange of ambassadors could certainly improve the relationship.

AS/COA: President Hugo Chávez was seen by the U.S. as a destabilizing force in Latin America. Will his successor continue to be seen in the same way?

Farnsworth: The proof is in the pudding. Washington is certainly interested in a better relationship with Caracas, but will be guided by the policies pursued by the next government. A continuation of Caracas' previous approach to the region, however, is uncertain, especially if Venezuela's deteriorating economy becomes a priority for Chávez's successor. If so, it's entirely conceivable that Venezuela's petro-diplomacy across the region could be de-emphasized, leading to a re-evaluation by regional governments of the benefits of aligning too closely with Caracas.

AS/COA: Chávez formed ties with countries that have tense relations with the United States. Do you see continuity in that policy under the new government?

Farnsworth: Chávez has prioritized building relations with Iran during his tenure. By so doing, Chávez increased his own personal profile but it is unclear how such a relationship has benefitted Venezuela as a nation. Arguably, it has not. With that in mind, transition in Venezuela's leadership could be an opportune moment to reduce the relationship with Iran and that would certainly have a positive impact with regard to Venezuela's relationship with the United States.

Eric Farnsworth is vice president and head of the Washington D.C. office at Americas Society and Council of the Americas.

"Venezuela's Uncertain Political Transition" - Christopher Sabatini, Senior Director of Policy, AS/COA

AS/COA: What are the most pressing issues that President Hugo Chávez's successor will face?

Christopher Sabatini: Whoever it will be, President Chávez's successor will face a set of daunting challenges. First among them will be the economy. In order to win reelection, President Chávez pumped up public spending in 2012, and Venezuela now confronts inflation running near 20 percent a year and a fiscal debt that equals over 15 percent of GDP. The state will have to retrench in terms of spending, just at a time when any successor will need to maintain popular support. At the same time, Venezuela's currency—the bolivar—is overvalued, hurting non-oil exports and local industry. A devaluation will have to come soon, but that will raise prices of imported goods—which the economy depends on because of inefficiencies in supply and the local market—and slow economic growth. At the same time oil exports have declined and the independence of the Central Bank and the state-owned oil company PDVSA have been undermined, hurting the capacity of the state to save and—in the case of oil—invest in technology and infrastructure to maintain already-decreasing production levels. Second are Venezuela's polarized politics. As the October 7 presidential election results demonstrated, Venezuela is a deeply riven country. Both sides are fractured and heterogeneous, further complicating the task of governing. While Chávez's nominal party—the PSUV—will likely remain unified in the early months of any transition, it remains a complicated coalition of forces from army officers, business leaders, to grassroots groups and fringe leftist parties.

AS/COA: Is there a future for a Bolivarian movement in Venezuela and in Latin America without Hugo Chávez at the helm?

Sabatini: Because it will have to, the movement will seek to maintain unity during the transition after Chávez. Don't look for any splits to erupt early in the process, simply because the various currents and factions within Chávez's PSUV know they face an energized (though also fragmented) opposition. For the last 13 years, the movement has been held together by President Chávez's charisma and his micromanagement and balancing of the competing demands and interests. But charismatic authority has difficulty replicating itself, and the two most likely leaders of the post-Chávez party—Nicolás Maduro and Diosdado Cabello—lack the current president's charisma and authority within the party. Moreover, Chávez was never an institution builder, preferring to govern by personal caprice. This means that the PSUV lacks many of the institutional means to resolve internal conflicts and select leaders across the various factions that it comprises. As a result, as economic and political decisions become more difficult and as a future president is forced to make tradeoffs among allies and make unpopular decisions, many of the factions and rivalries will surface and compete for the mantle and legitimacy of the movement. In short, the leader will be forced to contend with governing not just the country but his own party as well.

AS/COA: What's the outlook for Venezuela's foreign relations in a scenario where the PSUV remains in power?

Sabatini: It will be difficult if not impossible for any PSUV successor to fully unwind Chávez's network of patronage—even with the constraints of declining production and declining global prices. But without the figure of Chávez, ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance of the Americas) will have lost an important symbolic and very public leader. There is no one in the other countries who can match Chávez's flamboyance on the international stage, his at times clownish anti-Americanism or his passion for re-creating a hemispheric bloc parallel to his hero, independence leader Simon Bolivar. Cuba is particularly worried that it will lose the 80,000 to 120,000 barrels of oil it receives basically free from Venezuela which have kept the bankrupt Castro regime afloat for the last 13 years. The Dominican Republic and Jamaica—both huge beneficiaries of Chávez's largesse—are also worried. But whether it's ALBA or Petrocaribe, Venezuela's petro-patronage will remain; it is a centerpiece of the government's foreign policy. For one, it needs to continue to buy support internationally, and its alliances with Cuba, Bolivia, and Ecuador are an essential part of its reason for existence. Moreover, the hundreds of Cuban doctors and advisors that are in Venezuela—nominally in payment for the lifeline the government has thrown it—are essential to the Venezuelan government, and cannot be easily turned away. In sum, post-Chávez PSUV foreign policy will continue; it will just have lost its most identifiable, vitriolic public face and inspiration.

Christopher Sabatini is senior director of policy at Americas Society and Council of the Americas and editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly.

Timeline of Developments Since Chávez Disappeared from Public Stage:

- June 30, 2011: President Hugo Chávez tells the public that he underwent surgery in Cuba to remove a cancerous tumor. He undergoes several rounds of treatments over the following year and a half.

- December 8, 2012: Chávez announces that his cancer returned and that he would undergo surgery in Havana, Cuba. The president appoints Vice President Nicolás Maduro as his would-be successor.

- January 4, 2013: In an interview, Vice President Nicolás Maduro says that Chávez’s inauguration is a mere formality, and that his term would automatically begin on January 10.

- January 8: National Assembly President Diosdado Cabello reads a letter from Maduro announcing Chávez’s absence on inauguration day. The National Assembly passes a resolution authorizing Chávez to remain in Cuba, giving him time to recover before taking office.

- January 9: The Supreme Court issues a ruling saying that Chávez’s administration would continue despite a delayed swearing-in.

- January 10: On the scheduled inauguration day, Maduro and other party leaders lead a rally in support of Chávez, with the presidents of Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Uruguay in attendance. Representatives from 22 Latin American and Caribbean countries sign a declaration in support of Chávez's presidency and to support regional collaboration to avoid "destabilization" in Venezuela.

- January 11: Secretary General of the Organization of American States José Miguel Insulza issues a statement on January 11 saying that the regional institution "fully respects" Venezuela's decision about the inauguration.

- February 8: Finance Minister Jorge Giordani announces that the government devalued the bolivar by over 46 percent, bringing the value to 6.30 to the dollar.

- February 15: Information Minister Ernesto Villegas publicizes two photographs of Chávez in recovery, the first images of the president since he left for surgery in December.

- February 18: Maduro announces that Chávez returned to Caracas to continue treatment at a military hospital. Chávez’s Twitter account issues the first tweets since November 1 celebrating his return. A source from the Supreme Court says that justices are ready to swear in Chávez “at any moment.”

- February 28: The vice president says that Chávez “is battling there for his health, for his life.” The next day, Maduro affirms that Chávez has received “tougher” treatments—including chemotherapy— since his return to Venezuela.

- March 4: In a televised statement, Information Minister Ernesto Villegas says that Chávez has a "new and severe" lung infection.

- March 5: In the afternoon of March 5, Maduro declares that Chávez is suffering his "most difficult hours" since his December operation. The vice president also announces U.S. military attaché Colonel David Delmonaco would be expelled from Venezuela on charges of espionage. He adds that "special measures" would be taken to avoid plots against Chávez's administration. Later in the afternoon, the vice president announces Chávez's death at a military hospital in Caracas. Foreign Minister Elías Jaua says that Maduro would become acting president and that elections would be held within 30 days.

- March 8: Heads of state from across Latin America attend Chávez's funeral. In the evening, Maduro is officially sworn in as acting president. The opposition say that this is unconstitutional, since Chávez never took the oath of office. According to the Constitution, the head of the National Assembly should take over if the president is unable to be sworn in. Venezuela's Supreme Court ratifies Maduro as acting president, and rules that he can continue to serve while running for office.

- March 9: Venezuela's National Electoral Council announces the presidential election will take place on April 14.

- March 10: During a press conference, opposition leader and Miranda state Governor Henrique Capriles says he will run for president against Maduro.

- April 2: Presidential campaigns officially begin, according to the CNE's rules.

- April 11: Official campaigns end, though the opposition says the government broke electoral law by continuing Maduro's campaign on TV.

- April 14: The CNE announces that with 99 percent of the votes counted, Maduro wins with 50.66 percent against Capriles' 49.07 percent. But with a margin of less than 2 percent, Capriles refuses to concede. He calls for a recount, saying there were irregularities that took place at the polls. CNE President Tibisay Lucena says the results are "irreversible."

- April 15: The CNE releases the second vote bulletin with 99.17 percent of the votes counted. According to this report, Maduro won with 50.75 percent and Capriles earned 48.98 percent. In a televised statement, Capriles calls for the swearing-in to be postponed, and asks supporters to march with him as he goes to the CNE to ask for a recount. In the afternoon, Lucena proclaims Maduro the winner. She says the CNE will not carry out a recount, noting that an audit of 54 percent of voting stations had already taken place in accordance with electoral procedures.

- April 16: Jorge Rodríguez, head of Maduro's campaign, confirms the president-elect will be sworn in on April 19. Maduro says he will not allow Capriles and the opposition to march to the CNE, saying it was time for a "tough hand." Local media reports that at least seven died in post-election clashes. "If they [the opposition] continue with the violence, I'm ready to radicalize this revolution," says Maduro. At an afternoon press conference, Capriles discusses allegations of voting irregulaties, but calls off the march.

- April 18: Maduro heads to Peru to attend an emergency meeting of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) about the situation in Venezuela. The CNE agrees to an audit of the remaining 46 percent of votes from the April 14 election.

- April 19: UNASUR backs Maduro's win, as well as the vote audit. It creates a commission to investigate post-election violence. Latin American heads of state arrive in Caracas for Maduro's inauguration. Maduro is sworn in to office. During the inauguration, a man runs on stage and tries to grab the microphone from Maduro. "They could have shot me; security has failed," Maduro says.

- April 21: Maduro announces his cabinet, replacing about half of Chávez's ministers. He splits the finance and planning ministries, making Central Bank President Nelson Merentes head of the finance ministry, and appointing former Finance Minister Jorge Giordani as head of the planning ministry. Oil Minister Rafael Ramírez, Defense Minister Diego Molero, and Foreign Minister Elías Jaua stay on, as well as Vice President Jorge Arreaza.

- April 22: In an interview, Capriles says there is enough evidence from the vote audit to merit new elections.

- April 24: During a press conference, Capriles announces that the opposition will wait until April 25 for the government to begin the vote audit before taking further action. He also says the government "stole the elections." Venezuela's Congress opens an inquiry on Capriles' alleged involvement in post-election violence.

- April 25: Capriles says he will challenge the election results in the Supreme Court, and potentially in an international court.

- April 27: The CNE says it will not conduct a full audit to include voter registries and fingerprint data, which the opposition claimed would prove some people voted multiple times.

- April 29: The partial vote audit begins, though Capriles calls it a "joke."

- April 30: In the National Assembly, a fight breaks out resulting in several injuries. It begins after opposition congressmen hold up a sign of protest against a ruling that removes most of their parliamentary powers until they recognize Maduro's win.

- May 2: Capriles files an appeal to the Supreme Court to challenge the election results.

- June 9: The CNE announces that it completed the audit, confirming Maduro's victory. The opposition maintains that a full recount should have been realized.

The Presidency of Hugo Chávez

[[nid:48835]]

View an AS/COA slideshow of Chávez's 14-year presidency.

Key Players in Venezuela's Political Scenario

- Nicolás Maduro: Named by Chávez as his successor, Venezuela’s vice president ran as the ruling-party candidate when new presidential elections took place. Maduro served as interim president following the president's death. From 2006 to 2012, Maduro served as foreign minister, when he helped repair ties with Colombia and forged closer relations with Latin American allies such as Cuba and Ecuador. Appointed vice president in October, some observers described him as an unofficial “stand-in president” since Chávez underwent surgery on December 11. The CNE said he won the April 14 election with 50.75 percent of the vote, and proclaimed him the winner. He was sworn in as president on April 19.

- Diosdado Cabello: Elected president of the National Assembly last year, Cabello was reelected on January 5. A former lieutenant in the army, he has strong support from the Venezuelan military. He is also a member of the ruling party elite, serving as vice president of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. On the campaign trail, Cabello gave his support to Maduro.

- Henrique Capriles: The governor of Miranda state—who ran against Chávez in the October 2012 presidential election—ran as the opposition candidate against Maduro in the April 14 election. He won 49.07 percent of the vote and refused to concede, calling for a recount and alleging irregularities during the election.

- The Opposition: During the campaign leading up to the April 14 election, opposition leaders said the government broke election laws. While Chávez was ill, the opposition Coalition for Democratic Unity (MUD) called for Venezuelan leadership to provide more information on the leader’s condition and to follow constitutional procedures.

- The Military: Following Chávez’s death, Defense Minister Diego Molero Bellavia gave his support to Maduro and urged voters to choose the interim president. However, experts say Maduro lacks the close ties with the military that Chávez held.

- Adán Chávez: The president’s brother, who serves as governor of Barinas state, could potentially play a role in Venezuela’s politics. When the president first revealed that he had cancer and went for surgery in Cuba in June 2011, Adán “occupied the political void” and provided updates about Chávez’s recovery. Adán traveled to Cuba on January 2 following Chávez’s most recent surgery, but did not speak publicly about the visit.

- Cilia Flores: Venezuela’s attorney general and the vice president’s wife, Flores had said that Chávez could be sworn in by the Supreme Court at a later date. She counts among those who said Chávez was still the acting president whose term would begin January 10 even if he missed the inauguration.

- The Supreme Court: Justices from the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (also known as the TSJ) issued a ruling on January 9 authorizing Chávez to be sworn in at a later date. Supreme Court President Luisa Estella Morales said that Chávez’s new mandate would begin on January 10, and that the swearing in was a formality.

- The Catholic Church: On January 7, Venezuelan bishops issued a statement warning against changing the Constitution, saying it would be "morally unacceptable." They had said Chávez’s prolonged absence puts "at grave risk the political and social stability of the nation." Church leaders also called for more information about Chávez’s illness.

Ante estrecha victoria electoral se cuestiona si Nicolás Maduro liderará desde el pragmatismo que los venezolanos han clamado, escribe Christopher Sabatini y Andreina Seijas para El Tiempo.

Ahead of Venezuela's April 14 presidential election, five experts shared their views on what lies ahead for the Andean country's next leader.

AS/COA provides an overview of important dates, a rundown of candidates, and explanations of key institutions and voter blocs.