Six Facts to Understand Mexico's 2025 Judicial Elections

Six Facts to Understand Mexico's 2025 Judicial Elections

From candidate totals to voter turnout, learn about the country’s unprecedented election.

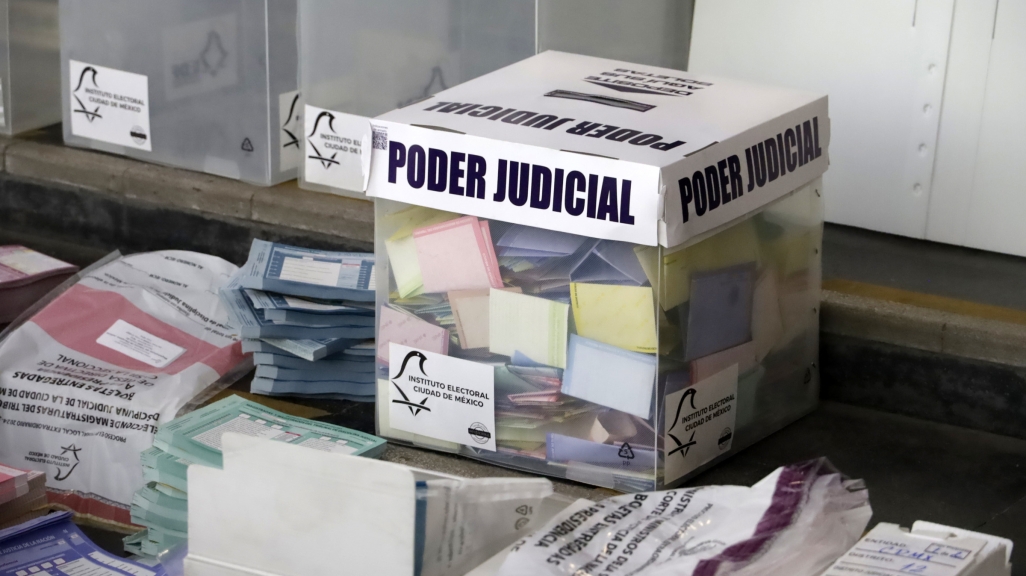

Mexico kicked off June by taking an unprecedented step: holding a national election to select the members of not only its Supreme Court, but also hundreds of federal and state-level judges and magistrates. The vote was novel, not only because it was the first of its kind since the Mexican government passed a judicial reform in September 2024, but also because no other country has such sweeping judicial elections. Bolivia holds direct elections for members of its highest courts while some U.S. states elect local justices. Mexicans, on the other hand, elected roughly half of their 1,600-strong federal judiciary on June 1 and will elect the remainder in 2027. Hundreds of other state-level judicial posts were also elected on Sunday.

The new election process has not been without controversy. The reform, an initiative of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, was presented and approved during his last month in office, leaving the government and his successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, with a complex inheritance, given that the selection of thousands of candidates and these first-time national elections took place within just eight months of AMLO leaving office. Sheinbaum and her party, Morena, have argued that the elections are a sign of true democracy and will help eradicate the corruption and nepotism in the country’s judiciary. But critics contend that the politicized process will allow the ruling party to extend its sway over the judicial branch, pave the way for less-qualified candidates to gain roles, and open the door to organized crime expanding its influence over courts.

Whatever the outcome, we will see how the electoral experiment pans out come fall: The judges and magistrates take office on September 1.

To help shed light on this singular process, here are six facts and figures to explain Mexico’s June 1 judicial elections.

"What Mexico is doing is like an experiment, and we don’t know what the outcome of it will be," said AS/COA's Carin Zissis to the Associated Press.

What can Mexicans expect from votes for judges in 2025 and 2027? What other constitutional amendments are on the horizon?