Reproductive Rights Update: A Regional Shift

Reproductive Rights Update: A Regional Shift

Over the past few years, abortion laws have changed significantly in several Latin American countries as governments respond both to the high number of unsafe procedures and demands for greater restrictions by the Catholic Church.

This week activists from around the hemisphere will come to Arequipa, Peru, for the First Latin American Legal Congress on Reproductive Rights—a conference sparked, in part, by recent policy changes affecting abortion rights. Over the past few years, abortion laws have changed significantly in several countries as governments respond both to high levels of unsafe abortions and demands for greater restrictions by the Catholic Church.

This update looks at recent disputes over abortions laws and the overall status of such legislation from around the hemisphere.

- Abortions in the Americas

- Legal Limbo in Colombia

- Peru: Legislation Sparks Protest

- Abortion Legislation at the Regional Level

Globally, Latin American and Caribbean countries have some of the strictest abortion laws. Abortion is legal “under broad criteria” only in Cuba, the French Antilles, French Guyana, Guyana, Barbados, and, as of August 2007, Mexico City. In most of the region, abortions are permitted in extreme cases, including rape, incest, or when the woman’s life is in danger. But in some countries, such as El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic, the procedure is prohibited in all cases—even when the mother’s life is at risk.

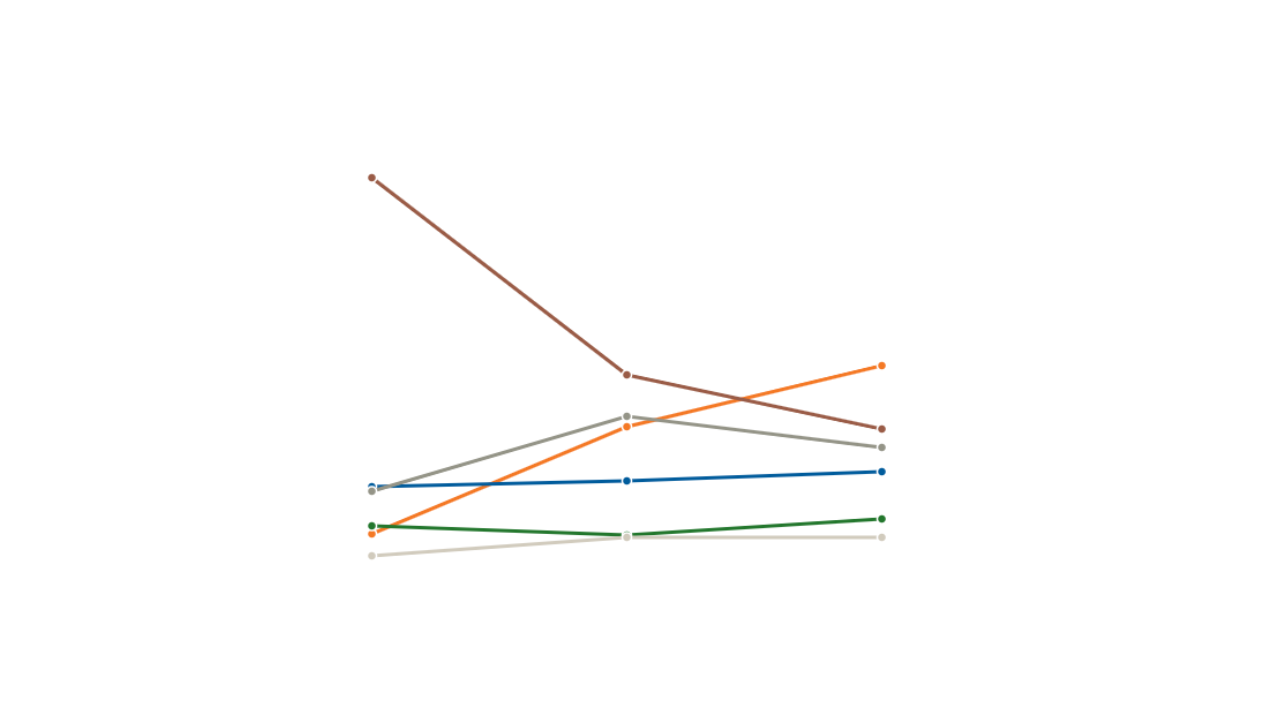

The region’s highly restrictive abortion laws seem to have little effect on the number of abortions carried out. The Guttmacher Institute estimates that there were 4.1 million abortions performed in the region in 2003, or 31 abortions for every 1,000 women between age 15 and 44. (In Europe, where abortion is generally legal, 28 women per 1,000 undergo the procedure.) Of the abortions performed in Latin America, 95 percent occurred under unsafe conditions, prompting many countries to introduce legislation to loosen restrictions on abortion and emergency contraception. Such efforts have met with mixed degrees of success.

The Constitutional Court and the legislature are deadlocked in Colombia over who has the last say in abortion laws. In 2006, the Constitutional Court legalized abortion in cases of rape, fetal deformity, and when the mother’s health is at risk. Under such circumstances, the Court mandated that abortions be covered by the state-mandated Obligatory Health Plan (Plan Obligatorio de Salud). Physicians who refuse to perform the procedure are required to recommend doctors who would be inclined to work with the patient.

But several reports have surfaced of doctors denying abortions to patients without providing alternatives. Among the most notable case was that of a 13-year-old rape victim denied access to an abortion in 2008 by seven hospitals. In response to such cases, last month the Court ordered a national education campaign on sexual and reproductive rights, including the right to an abortion under the Court-stipulated conditions.

This new initiative brought the abortion debate again into the national spotlight. On October 22, Colombian Attorney General Alejandro Ordoñez, a public opponent of abortion, requested that the original Court decree be nullified and the sexual education campaign stopped. The State Council suspended the Court ruling, saying that it needed to be corrected and properly defined.

The suspension has left abortion in a legal limbo. The Court’s verdict on the decriminalization of abortion is still in effect, but it is unclear how doctors, clinics, and other health providers should act until the State Council reviews the case. The result: a brewing conflict between the Court and the legislator. According to Mónica Roa, director of the Gender Justice Program at Women's Link Worldwide: “The Supreme Court ruling is clear, but in practice it’s unclear for women and for the EPS [Colombia’s health insurance providers] whether clinics are obligated to provide service while the law is suspended.” Roa believes that the State Council could take between seven and nine years to reach a decision.

Peru: Legislation Sparks Protest

Hundreds of protesters both in favor of and against liberalization of abortion laws took to the streets in October after the Special Congressional Committee of the Revision of the Penal Code recommended the decriminalization of abortion in cases of rape and fetal deformity. The Committee gave its approval for the motion to go before the president of the Congress, Luis Alva Castro; he will now decide whether to put the bill before Congress. Currently, abortion is illegal in Peru except when pregnancy threatens the life of the mother.

In the same week as the Committee’s recommendation, Peru’s Constitutional Court banned the free distribution of emergency contraception. Free distribution of the pill, commonly known as the “morning-after pill,” was stopped because the Court claimed insufficient proof that the pill is contraceptive, rather than abortive. It is still legally available—although at a cost—in clinics. The Court’s decision has divided the presidential cabinet: the ministers of health and social protection say it discriminates against the poor, while the minister of defense celebrated the ruling.

Abortion Legislation at the Regional Level

Beyond the clashes in Peru and Colombia, other efforts to loosen restrictions on abortion and emergency contraception have been met with resistance. In Mexico, in what is widely seen as a backlash to the 2007 decision in Mexico City to legalize abortion in the first trimester, 16 states have amended their constitutions to define life as beginning at conception. In Chile, President Michelle Bachelet’s relatively liberal social agenda did not affect the country’s status of having among the region’s strictest laws; abortion remains illegal even when the mother’s life is at risk. Last year, Chile’s Constitutional Court overturned the President’s 2007 decree to make emergency contraception available for free in public clinics. Also in 2008, Uruguayan President Tabaré Vázquez vetoed a bill—despite it having 60 percent of public support— that would have decriminalized abortion in the first trimester.