Killing a Trade Pact

Killing a Trade Pact

The isolated killings of union members in Colombia do not justify holding up a U.S.-Colombia trade agreement, writes Edward Schumacher-Matos, a former foreign correspondent for the New York Times and a visiting professor of Latin American studies at Harvard University.

President Bush has been urging Congress to approve a pending trade agreement with Colombia, an ally that recently almost went to war with Venezuela and Hugo Chávez. Even though the agreement includes the labor and environmental conditions that Congress wanted, many Democrats, including Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, now say that Colombia must first punish whomever has been assassinating the members of the nation’s trade unions before the agreement can pass.

An examination of the Democrats’ claims, however, finds that their faith in the assertions of human-rights groups is more righteous than right. Union members have been assassinated, but the reported number is highly exaggerated. Even one murder for union organizing is atrocious, but isolated killings do not justify holding up the trade agreement.

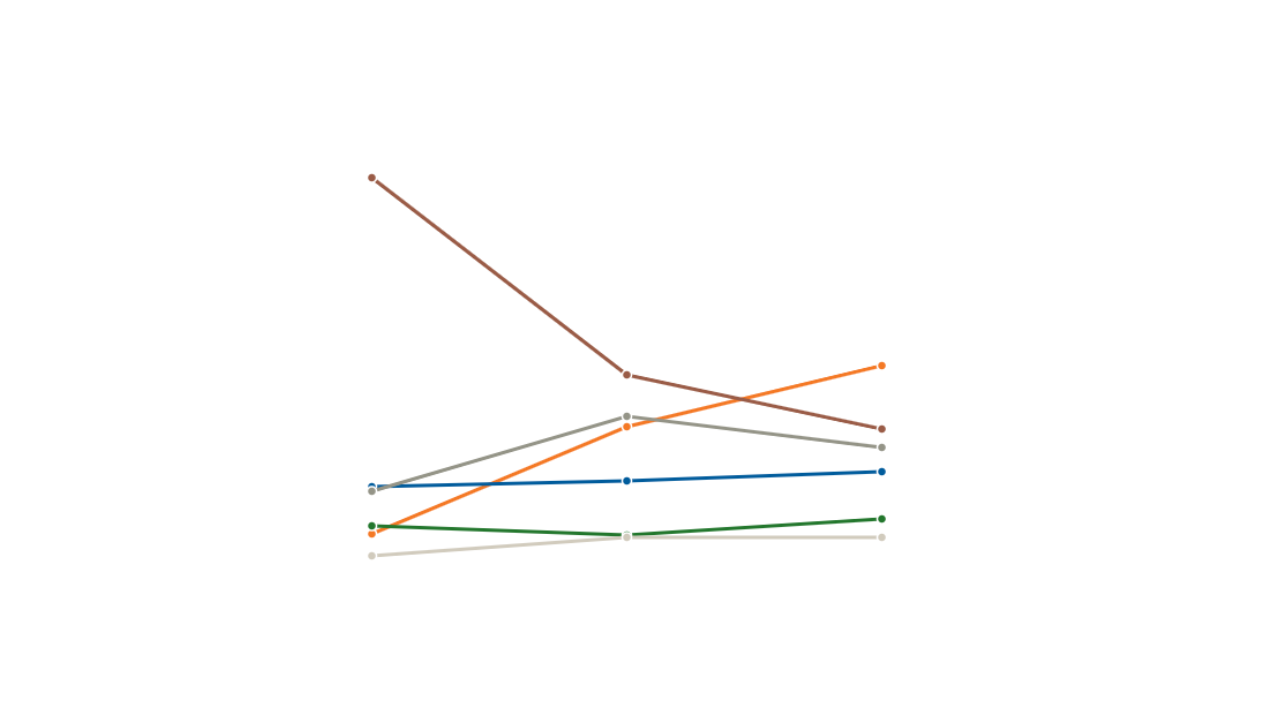

All sides agree that trade-union murders in Colombia, like all violence, have declined drastically in recent years. The Colombian unions’ own research center says killings dropped to 39 last year from a high of 275 in 1996.

Yet in a report being released next week, the research center says the killings remain “systematic” and should be treated by the courts as “genocide” designed to “exterminate” unionism in Colombia. Most human-rights groups cite the union numbers and conclude, as Human Rights Watch did this year, that “Colombia has the highest rate of violence against trade unionists in the world.”

Even if that is true, it was far safer to be in a union than to be an ordinary citizen in Colombia last year. The unions report that they have 1 million members. Thirty-nine killings in 2007 is a murder rate of 4 unionists per 100,000. There were 15,400 homicides in Colombia last year, not counting combat deaths, according to the national police. That is a murder rate of 34 citizens per 100,000.

Many in Congress, moreover, assume that “assassinations” means murders that are carried out for union activity. But the union research center says that in 79 percent of the cases going back to 1986, it has no suspect or motive. The government doesn’t either.

When the Inter American Press Association several years ago investigated its list of murdered Colombian journalists, it found that more than 40 percent were killed for nonjournalistic reasons. The unions have never done a similar investigation.

There are, however, a growing number of convictions for union murders in Colombia. There were exactly zero convictions for them in the 1990s, Colombia’s bloodiest decade, when right-wing paramilitaries and leftist guerrillas were at the height of their strength. Each assassinated the suspected supporters of the others across society, including in unions.

With help from the United States, in 2000 the Colombian military and the judicial system began to reassert themselves. Prosecuting cases referred by the unions themselves, the attorney general’s office won its first conviction for the murder of a trade unionist in 2001. Last year, the office won nearly 40.

Of the 87 convictions won in union cases since 2001, almost all for murder, the ruling judges found that union activity was the motive in only 17. Even if you add the 16 cases in which motive was not established, the number doesn’t reach half of the cases. The judges found that 15 of the murders were related to common crime, 10 to crimes of passion and 13 to membership in a guerrilla organization.

The unions don’t dispute the numbers. Instead, they say the prosecutors and the courts are wasting time and being anti-union by seeking to establish motive — a novel position in legal jurisprudence.

The two main guerrilla groups have an avowed strategy of infiltrating unions, which attracts violence. About a third of the identified murderers of union members are leftist guerrillas. Most of the rest are members of paramilitary groups — presumed to be behind two of the four trade unionist murders this month. The demobilization of most paramilitary groups, along with the prosecutions and government protection of union leaders, has contributed to the great drop in union murders.

President Álvaro Uribe, who has thin skin, can be unwisely provocative when responding to complaints from unions and human rights groups. Still, the level of unionization in Colombia is roughly equal to that in the United States and slightly below the level in the rest of Latin America. The government registered more than 120 new unions in 2006, the last year for which numbers are available. The International Labor Organization says union legal rights in Colombia meet its highest standards. Union leaders have been cabinet members, a governor and the mayor of Bogotá.

Delaying the approval of the trade agreement would be convenient for Democrats in Washington. American labor unions and human-rights groups have made common cause to oppose it this election year. The unions oppose the trade agreement for traditional protectionist reasons. Less understandable are the rights groups.

Human Rights Watch says that it has no position on trade but that it is using the withholding of approval to gain political leverage over the Colombian government. Perversely, they are harming Colombian workers in the process. The trade agreement would stimulate economic growth and help all Colombians.