Explainer: Bolivia's 2025 Elections

Explainer: Bolivia's 2025 Elections

Intersecting political and economic woes could end 20 years of MAS rule. We explore the presidential candidates and legislative competition.

Bolivians will soon head to the polls for elections defined by a bitter split between leaders of the ruling party along with an economy marked by shortages of basic goods and soaring food prices. In this turbulent context, opposition candidates hope to convince the electorate to end two decades of almost uninterrupted governance by the Movement for Socialism, better known by its Spanish acronym MAS.

The first round of the presidential vote, as well as elections for both houses of Congress, will take place on August 17. Just over 7.9 million Bolivians are eligible to cast ballots, including around 370,000 residing abroad. If no candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote, or 40 percent with at least a 10-point advantage over the runner-up, a runoff will be held on October 19. Officials will be sworn in for five-year terms on November 8.

Out of the running are both incumbent President Luis Arce (2020–present) and ex-President Evo Morales (2006–2019), the MAS’ emblematic former leader who resigned from the presidency in 2019 after his electoral victory was disputed due to suspected fraud. Meanwhile, Arce dropped out of the race in May 2025 with polls showing low levels of support, while judicial and electoral authorities have enforced Morales’ ineligibility to vie for a fourth presidential term.

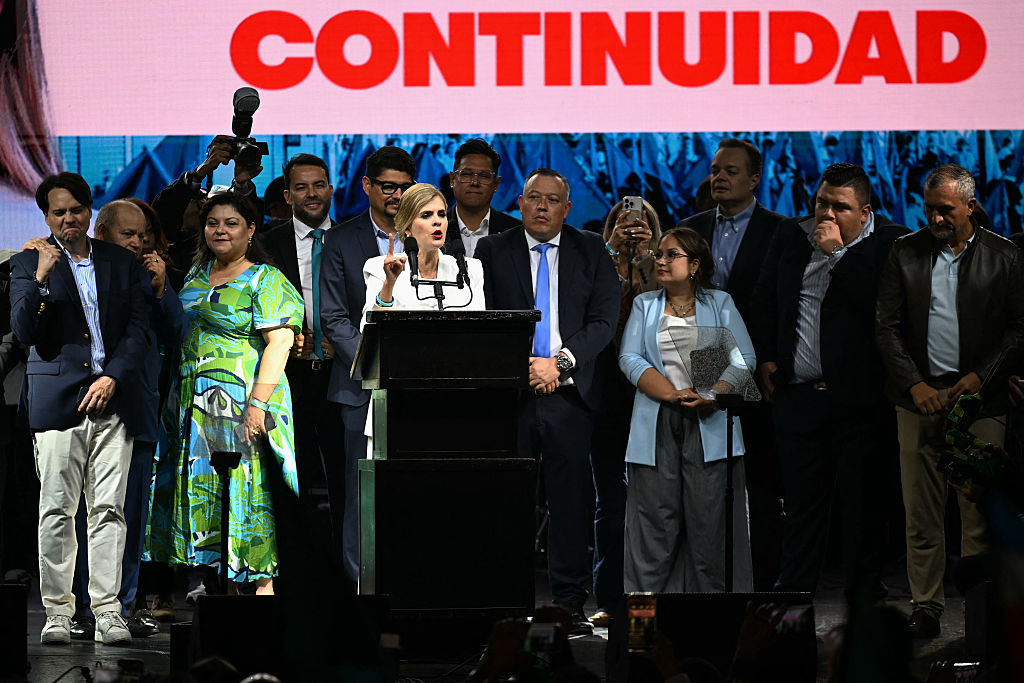

Of the eight hopefuls on the presidential race, center-right candidate Samuel Doria Medina of the Unity Alliance and conservative ex-President Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga, of the Liberty Alliance, poll ahead in a race with high levels of undecideds and a crowded field. Aside from other opposition contenders, they face off against various figures from the left, including the MAS candidate Eduardo del Castillo, backed by incumbent Arce, and Senate president Andrónico Rodríguez, a former Morales protégé now supported by the Popular Alliance, who leads left-of-center options in the polls.

AS/COA Online lays out the political and economic landscape of Bolivia’s elections.

Amid economic turbulence and a presidential squabble, see polling for the August 17 first-round vote.

AS/COA covers 2025's elections in the Americas, from presidential to municipal votes.