Exclusive Interview: Juan Carlos Rulfo and Daniela Alatorre on the Making of ¡De Panzazo!

Exclusive Interview: Juan Carlos Rulfo and Daniela Alatorre on the Making of ¡De Panzazo!

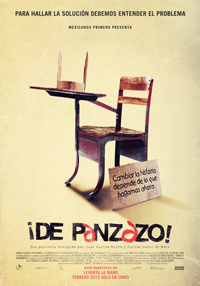

The director and producer talk with AS/COA Online about the Mexican documentary, which uncovers the urgent need for better education and teacher evaluations in Mexico.

As the documentary ¡De Panzazo! explains, Mexico is the OECD member that spends the most on education in terms of public spending, yet its education system ranks last in terms of quality. ¡De Panzazo! director Juan Carlos Rulfo and producer Daniela Alatorre spoke with AS/COA Online’s Carin Zissis after the film’s New York premiere on June 4 at Americas Society. With the support of civil society group Mexicanos Primero, the documentary calls for quality education and teacher evaluations in Mexico. Rulfo and Alatorre explain how they became involved in the project, involving Mexican students in the film’s production, the need to share best educational practices on an international level, and the impact of the film during a Mexican election year.

As the documentary ¡De Panzazo! explains, Mexico is the OECD member that spends the most on education in terms of public spending, yet its education system ranks last in terms of quality. ¡De Panzazo! director Juan Carlos Rulfo and producer Daniela Alatorre spoke with AS/COA Online’s Carin Zissis after the film’s New York premiere on June 4 at Americas Society. With the support of civil society group Mexicanos Primero, the documentary calls for quality education and teacher evaluations in Mexico. Rulfo and Alatorre explain how they became involved in the project, involving Mexican students in the film’s production, the need to share best educational practices on an international level, and the impact of the film during a Mexican election year.

AS/COA Online: As the film implies, Mexico’s educational challenges have a long history. What sparked the making of the film now?

Alatorre: So this was a process of three years. Mexicanos Primero had been working at least for three years, so that makes it six now. And they thought they needed to do something big that could talk to a broader audience. And so they talked to [Mexican news anchor] Carlos Loret. Then they said: “Why don’t we do a series of TV shows?”

Rulfo: …TV shows, TV reportages…

Alatorre: Then it wasn’t the right format, so they came up with the idea to make a film. They called Juan Carlos and myself. But we’re more into documentaries than film—Juan Carlos for many more years than I have, and with a lot of experience. They called me in, and then we created a great team. We worked for three years on this film.

And why now? Because it just seemed completely urgent to do it. There was no time left, and it had to be done.

AS/COA Online: Much of the film involves student participation, including students conducting interviews. What was behind the decision to involve them, and what was that process like?

Rulfo: Because I liked it! I mean, for me it’s very important to talk with the people, to reach the hearts of the people in some way, and not to try to make a kind of PowerPoint report. We need to know what the people say about their own problems, in that sense—not just experts.

AS/COA Online: How did you select the students to get involved?

Alatorre: There was a lot of help from the directors of schools. They were really brave and we had a great relationship with directors of certain schools. We told them what type of students we wanted to work with, and then they suggested a couple of people, and then we talked to them.

Rulfo: We were in a hurry in some ways, so we didn’t have lot of time to stay in the schools several weeks just to know the correct people—that’s a bit complicated.

Alatorre: We had a lot of small cameras, so there were a lot of students that did their video diaries that are not in the film. So we sort of selected afterwards which characters were going to stay in the film.

Rulfo: It was amazing. That was a good idea.

AS/COA Online: The film has drawn large audiences and strong responses. What are some of the concrete results you’ve seen stemming from the release of the film?

Alatorre: In terms of concrete results, I think, would be these small cards that we gave out during the theatrical release. There were 150,000 people who gave their names and emails on those cards, and now there is a database of people that want to get involved. And then there’s list of people that Mexicanos Primero is putting in a release, and saying, “These people signed this to have things change.” So you have names and email addresses of people saying, yes, I want to do something.

Probably the other thing, that we won’t be able to measure, is how much more involvement there is from the parents. That’s exactly what the film was supposed to encourage—how much parents, after watching the film, are going to their schools and asking the directors, the principals, the teachers about how the kids are doing. It has to be a much more active role that the parents play.

AS/COA Online: Given that the film is coming out during an election year in Mexico, do you have hopes for post-election changes based on this film? And how have the candidates responded?

Rulfo: I don’t know exactly about the strategies of the candidates. I mean, nobody is saying very specific or strong proposals that I know. But the point is Mexicanos Primero has a strategy to continue pushing and pushing in that way. In the past there were no other films that worked with the conscientiousness of the society. So the point, for me, could be to continue trying to make more films about that. Alatorre: This week the candidates are going to get together to answer specific questions about education. That is something that probably has been pushed by the release of the film, and because people are expecting these candidates to talk about education, not only “we promise quality of education”—which is what we’ve heard for years—but exactly what are they planning to do, because people are not going to take only a promise. Rulfo: Nobody is saying anything about the teachers, for example. Everybody says, yes, we have problems with the quality of education, but nobody is saying, hey, we need to promote finding teachers to try to make better students and people. Nobody is saying that.

AS/COA Online: The film has very much of a Mexican focus, and now you’re here to show it in the United States and get an international audience. How do you think you can engage international audiences, and what do you hope for in terms of an international response?

Rulfo: I would like to ask you. (Laughter.)

Alatorre: We knew that it was a very Mexican perspective since we started the film, and we thought that we need to do it with a Mexican perspective because it is for Mexican audiences. That was the intention from the beginning, to go theatrical, to go to TV.

And what we found is that, for example, with the United States, we have an incredible audience here, too—people that left Mexico or people that have Mexican families—and that it helps them understand what’s going on in their own country and how important education is. A lot of second-generation Mexicans are going to school, are doing wonderful careers, and now have incredible positions. They’re professionals, and they realize there can be social change. And that’s only because they’re able to have a good education and to start a career in the whole sense of the word.

Rulfo: It’s the beginning of a lot of things. It’s amazing. Nobody thinks in a small way like that: “Hey, I could change something?” Yeah, you could, you will if you try to start right now. So that’s the point.

At the same time everybody is saying it’s like [the U.S. film] Waiting for Superman. At the same time that’s also a very local film because it’s about the U.S. But at the same time, in several parts of the world, we have heard that in Argentina, in China, in Brazil, in France they are working on such films about education. So it’s something about the world.

AS/COA Online: In many of the film’s infographics, some of the other lower-ranking countries in terms of education were, unfortunately, Latin American countries. I was wondering if you’ve gotten responses from other filmmakers in Latin America.

Alatorre: Mexicanos Primero and also Worldfund work a lot with Brazil, and they also have a very particular focus on their education. So I think this film could also create a dialogue between different Latin American countries in terms of what’s going on in your country and what has worked in the past that could be a good road to go through, because this dialogue has to start. You cannot think that you are a country with no connections to other countries whatsoever. There has been a history where some countries have had a successful program, so why wouldn’t we dialogue in terms of successful programs? Brazil has very successful programs, and these things can be learned so that you don’t have to discover anything new; you can learn also from the experience of the other countries.

Rulfo: We need to.