Cuba's Five Issues to Watch in 2018

Cuba's Five Issues to Watch in 2018

Here’s what you need to know about an end to the Castro presidency, new migration rules, Russia ties, and more.

This will be a historic year for Cuba. In some ways it will mark a new era for the largest of the Caribbean countries, and in other ways, a return to the past. As we kick off the new year, here are issues to keep an eye on, from a new president to renewed Russia ties to the advent of the internet age on the island.

1. The presidency: The beginning of the end of los históricos

For the first time since 1959, Cuba won’t have a Castro president. Raúl Castro is set to step down as president on April 19. Fidel Castro’s brother will leave the presidency two months later than originally scheduled due to the setbacks brought on by Hurricane Irma.

The transition will be preceded by legislative elections for 605 seats in the unicameral National Assembly on March 11. On January 21, candidates for deputies will be nominated by the municipal assemblies, which were chosen during municipal elections in November. On the same day as the new National Assembly’s inauguration, the deputies will choose 31 of the assembly’s own members to compose the Council of State, which includes the president, the most senior first vice president, another five vice presidents, and a secretary.

In line to succeed Raúl is protégé Miguel Díaz-Canel, Cuba’s first vice president since 2013. Díaz-Canel, who will turn 58 the day after taking the presidency, will be 28 years younger than his mentor and, unlike many of his colleagues, is not part of the Revolution generation known as los históricos. The age difference is likely a more symbolic representation of the transition of power than an actual one. Though Díaz-Canel will be the head of the state and ministerial councils of the assembly, Raúl will maintain his position as the leader of the military and the Communist Party, which will lead Congress until the next elections in 2021.

Further, Díaz-Canel’s lack of a military background is part of a significant shift Raúl has been formulating since he expanded the number of assembly seats to incorporate younger politicians in the last elections, which took place in 2011. “Raúl is creating a civil, rather than military, government to succeed him, in order to…send a signal to the United States that things are changing,” Camilo Loret de Mola, a Cuban lawyer and Univision TV producer, told journalist María Elvira Salazar in November.

But when it comes to U.S.-Cuba ties, Díaz-Canel’s mindset mirrors los históricos’ view rather than the views of younger Cubans, 70 percent of whom support closer relations. In a video leaked in 2017, Díaz-Canel is recorded saying, “The U.S. government...that invaded Cuba, put the blockade [embargo] in place, and imposed restrictive measures will have to resolve these asymmetries if they want to normalize relations.”

2. Migration: Freedom to be Cuban again

As of January 1, foreign-born children of Cubans living abroad have the opportunity to apply for Cuban citizenship, and emigrants who left the country illegally will also be allowed back in. Cuban expats may now also enter and leave in recreational boats as long as they pass through one of two marinas: Havana’s Marina Hemingway or Varadero’s Marina Gaviota-Varadero.

The measures, approved in October 2017, are part of the government’s efforts to engage the Cuban diaspora, which numbers over 2 million, roughly 1.3 million of whom live in the United States. This expat community supplied the island with a record $3.4 billion worth of remittances in 2016, and sent 454,000 U.S.-based Cubans to visit their home country in 2017. In addition, the Cuban government will now forego a facilitation stamp on visas, known as la habilitación, drastically reducing the paperwork for the understaffed Cuban embassy in Washington, which has only one officer processing visas.

Still, caveats and contradictions abound in the new migratory rules. For example, applications could be declined for children of political dissidents. Plus, doctors and athletes who defected on a foreign tour do not get the same freedom of movement in and out of the country because they left legally, whereas the new permissions are extended to those who left illegally.

3. The economy: Ups and downs

Despite a record year for tourism, Cuba’s economy has taken hard hits, in large part from a drop in Venezuelan refined fuel imports, which fell 50 percent from 2013 to 2016. Venezuelan oil supplies fell another 13 percent in the first half of 2017, prompting Cuba to retake ownership of the 49 percent stake Venezuelan oil firm PDVSA had in the island’s Cienfuegos refinery.

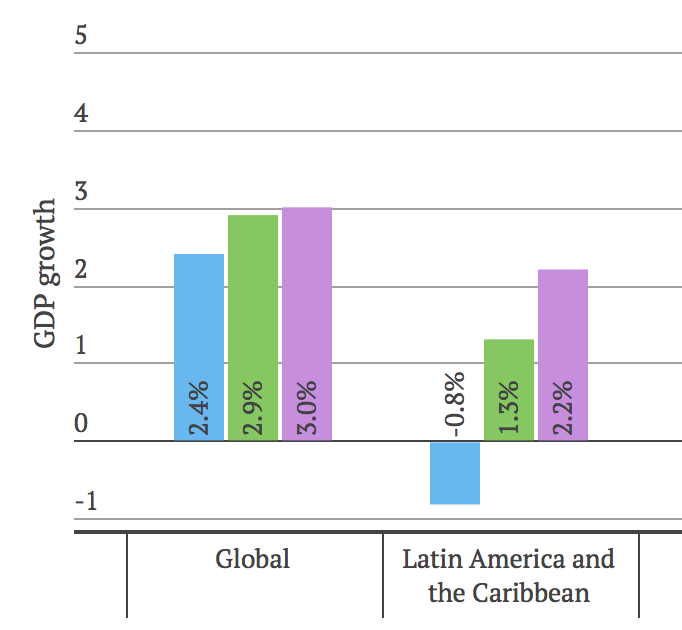

After an economic contraction in 2016, Cuba’s economy was back in the black in 2017 and is expected to double its GDP growth in 2018. A report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean forecasts 1 percent growth for 2018, compared to an estimated 0.5 percent in 2017. The Cuban government, on the other hand, announced rosier prospects, projecting a 2 percent economic expansion, citing improvements in the construction, commerce, and tourism sectors, as well as higher cigar and liquor exports.

Also, as of August 2017, the island’s once-burgeoning private sector has stalled, given that new applications for self-employed persons, known as cuentapropistas, were on hold indefinitely until the government curbs what it says are transgressions taking place, like making purchases in the black market. Meanwhile, the 568,000 cuentapropistas who make up the sector increasingly have difficulties getting supplies from empty store shelves—the reason they felt forced to turn to the black market in the first place.

Moreover, the Trump administration’s rollback of U.S.-Cuba relations is expected to hurt owners of paladares (small restaurants) and casas particulares (Airbnbs), since the new, stricter U.S. regulations require people to travel in tour groups that are more likely to stay in larger government-run hotels.

4. Foreign relations: New and old friends

Weaker relations with the United States and Venezuela have Cuba strengthening partnerships with former benefactor Russia and sealing new commercial ties with Europe. In May, Russia came to the rescue in Cuba’s energy crisis with its first oil shipment to the Caribbean country since the end of the Soviet Era. From January to September 2017, Russian exports to Cuba were 81 percent greater than in the same period in 2016. The two countries have projects in the works worth about $4 billion, including a contract to be signed this year for a high-speed rail connecting Havana to the popular Varadero beach resorts.

The European Union is also stepping in. In November, the EU officially normalized diplomatic relations with the island after signing a political dialogue and cooperation accord in 2016. In a two-day visit starting January 3, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini met with Raúl Castro and other government officials to discuss engagement and commercial agreements. “The EU is an important commercial, economic, and cultural partner and a distinguished source of tourists for Cuba,” said Foreign Affairs Minister Bruno Rodríguez. Mogherini said agreements worth $59 million in the areas of renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, culture, and professional expertise are forthcoming.

5. The internet: A different kind of bubble

The island may still be one of the worst places in the world to access the internet, but that doesn’t mean Cubans won’t try to get online. Just 39 percent of the country’s 11 million inhabitants use the internet. That low penetration rate, combined with the government’s censorship, scored the country a 79 on the Freedom House 2017 Freedom of the Net report—the fifth-worst score out of 65 countries in the ranking.

But starting at the bottom also means the country has seen some of the greatest jumps worldwide in things like social media and mobile phones, with the number of Cubans using social media on their cell phones rising 385 percent from 2015 to 2016. In 2017 alone, there were 600,000 new mobile phones for a total 4.5 million people on the island. On December 29, state telecommunications agency Etecsa announced that it would begin to offer internet service to cell phones in 2018, but without specifying any timeframe or price points. Today most Cubans connect to the internet via one of 500 public wifi hot spots, computers at schools, or the workplace of certain professions.

The ability to buy internet service for homes will be another novelty for the average Cuban this year, as the government extends a pilot program in Havana launched in 2016 called Nauta Hogar that for the first time allowed private citizens to log on from home. But being years behind the digital revolution means Cubans will start off with last century’s DSL technology, in which computers connect to the web via fixed telephone lines—a service only 8 percent of the island has. What's more, home internet is rationed to 30 hours per household a month.

So far some 11,000 households have the Nauta Hogar internet. How much that number will expand is uncertain given that the minimum monthly package costs $17 a month for 256 kbps speeds, and the best package $80 for 4 mbps. (The average residential broadband subscription worldwide costs $112 for 136 mbps.) The privilege will be nearly impossible to afford for the average Cuban, who makes about $30 a month, according the country’s National Office of Statistics and Information.