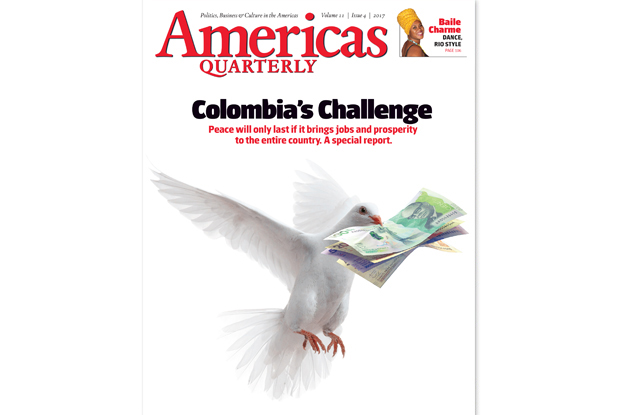

"Colombia's Challenges": A Policy Briefing and Recommendations from the New Issue of Americas Quarterly

"Colombia's Challenges": A Policy Briefing and Recommendations from the New Issue of Americas Quarterly

Read a policy briefing and recommendations from the new issue of Americas Quarterly.

Overview

To many outsiders, Colombia looks like a success story. Just 15 years ago, it was on the verge of becoming a “failed state”—besieged by kidnappers, guerrillas, and cocaine kingpins. Since then, violence and unemployment have plummeted. In 2016, President Juan Manuel Santos struck a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)—and won the Nobel Peace Prize.

However, to many Colombians, that rosy narrative is out-of-date—and out-of-touch.

The economy has been struggling for years with sluggish growth amid low prices for exports, especially oil. Numerous corruption scandals have eroded the credibility of the entire political class—which in a September poll enjoyed popular approval of just 7 percent, a third the level in February. Infrastructure remains among the world’s worst, with quality of roads ranking just 120th out of 138 countries in a recent global study. Cocaine production is soaring once again, and new violence has broken out in areas including Nariño, near the Pacific coast. Meanwhile, Colombia continues to struggle with its age-old gap between haves and have-nots—in Latin America, only Haiti suffers from greater inequality.

The new issue of Americas Quarterly explores Colombia’s current challenges and opportunities, with articles authored by a range of policy experts and journalists. The main takeaway: That for peace to take hold, Colombia’s government and private sector should focus on increasing job creation in all regions of the country, especially those where guerrilla groups were once dominant.

Policy Recommendations

1. Colombia’s next government should increase the focus on quickly creating jobs and infrastructure in former guerrilla strongholds.

There are vast swathes of Colombia that have never known peace. That may seem like an overstatement, but it’s true—a result of the country’s exceptionally challenging geography, a historically weak and under-resourced federal government in Bogota, and the vast reach of armed non-state actors (a problem that long predates the FARC). The future of the peace deal will depend on how quickly economic development comes to these mostly rural, long-abandoned areas. As one expert told AQ: “If you don’t generate prosperity in these territories, if you don’t generate jobs and sources of legal income, then it’s going to be a lot harder for peace to take hold.”

The current government’s Territorially Focused Development Program (PDET in its Spanish acronym) is an ambitious agenda to spend $38 billion on infrastructure (roads, schools, health clinics, aqueducts, Internet connections, and power lines), grant land titles to peasants, and provide monthly stipends to farmers to uproot coca and replace it with food crops. However, several experts told AQ that “the government’s inability to operate with any real agility” is making it difficult for this “rural metamorphosis to take shape.” A government official added: “We need to do some important investments this year. That would send a message that this peace process is really happening.”

These concerns, plus recent violence in areas like the Pacific coast, have added to a dangerous sense of drift among some Colombians. If left unchecked, it could effectively cancel out the positive effects of the 2016 peace agreement and cause bloodshed to increase once again.

In that light, Colombia’s next government (to be elected in June 2018) should resist the temptation to dismiss the implementation of the FARC deal as “President Santos’ project.” Instead, it should direct as many resources as possible to infrastructure in at-risk areas, while also removing bureaucratic hurdles. One good example covered in AQ is electricity: Despite the government’s $4.3 billion PaZa la Corriente program to address the 425,000 households that lack coverage, electrical demand is expected to continue to outpace supply in coming years. To address this, the government could simplify the consultative process in which towns and indigenous communities meet with the government to determine which projects should go forward (a whopping 11,000 such meetings are scheduled in coming months). It could also revise regulations to make it easier for clean energy producers and small-scale producers to generate electricity to sell back to the grid. Solutions are not only about money.

2. The United States should continue to assist Colombia’s effort to create legal employment in at-risk areas. Doing so will help curb the substantial recent increase in coca production.

The $10 billion in U.S. support under Plan Colombia since 2000 has been critical to Colombia’s success. Congress’ approval of $450 million in initial support for Peace Colombia should help ensure continued progress. However, the recent sharp rise in coca cultivation has called this bipartisan success story into question, and spurred some calls for Washington to take a “tougher line” with Bogota.

Now would be a terrible time to abandon Colombia or reduce assistance, since supporting economic development and infrastructure can be very effective tools in stemming drug cultivation. As departing U.S. Ambassador Kevin Whitaker told AQ: “Building even a basic road in some of these areas can be transformative in opening up parts of the countryside to licit economic activities.” One important tool will be to continue USAID’s development assistance in this sector. Part of USAID’s goals outline work in key areas to “create the preconditions for a vibrant rural economy” which includes encouraging greater public and private investment, financial inclusion, and supporting investment funds focused in Colombia’s rural economic sector. As producers and cooperatives grow in these areas, U.S. help could be critical to helping producers in sectors such as coffee, cacao, and rubber producers to tap into larger markets and buyers.

3. The private sector should invest in opportunities in demilitarized zones that will generate jobs and income, as well as financial returns.

Larger private sector investors have been slow to move into former guerrilla territories. As noted in AQ, companies can be counted on one hand—such as Starbucks, Colombian dairy company Alquería, and India’s Hero Motor Corp. There is potential to greatly expand private sector investment in demilitarized zones.

Some venture capital funds are supporting early-stage companies that can have an impact on marginalized and poorer communities by, in one example, sourcing cacao from smallholder farmers affected by the armed conflict. This is necessary for this stage of development. Coffee and cacao investments are early wins, but soon, investment will need to migrate into value-added, employment-intensive sectors to truly transform the economies of these rural areas and create diversified local economies.