Brazil Update: Congress to Take a New Shape in 2015

Brazil Update: Congress to Take a New Shape in 2015

On October 5, voters elected the most conservative legislature since the post-1964 period, as well as a larger number of political parties.

All eyes are on Brazil’s presidential race as President Dilma Rousseff and Senator Aécio Neves head to a runoff on October 26. But whoever wins will face a major challenge once in office: an increasingly fragmented legislature and a need for continued coalition-building. Because no party garnered more than 70 seats in the lower house, both the president and Neves’ parties would lack a majority in Congress. While the ruling Workers’ Party (PT) maintains a coalition that includes the large, centrist Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMBD), a greater number of parties in the lower house will mean more negotiating. Plus, changes may be afoot: the Brazilian Socialist Party—normally a PT ally—threw its weight behind Neves in the presidential race. The new legislative session begins on February 1 next year.

On October 5, Brazilians elected the most conservative Congress in the post-1964 period, according to the Intersyndical Parliamentary Assistance Department (DIAP), which monitors the legislature. DIAP found that more representatives tied to the military, religious groups, and agribusiness won election, while a fewer number of legislators focused on social causes gained seats. For example, the number of evangelical representatives in the Chamber of Deputies increased by 14 percent, with 80 lawmakers elected. This could jettison efforts to pass legislation on LGBT rights and abortion, O Globo points out. Meanwhile, the number of military and police elected to the Chamber of Deputies is slated to rise 30 percent and the number of deputies representing labor union interests will fall by nearly half, DIAP estimates. The so-called ruralistas—those who support agribusiness interests—will increase their seat count from 60 to 70.

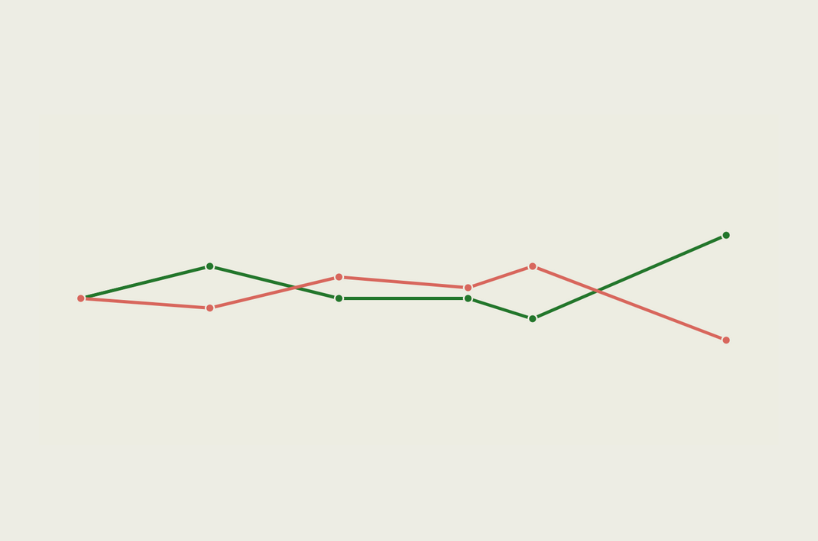

In an addition to an ideological shift, the Chamber of Deputies became more fragmented. The total number of parties in the lower house increased from 22 to 28, without a majority for neither the governing Workers’ Party (PT) nor the right-leaning Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). In the lower house, the PT lost the largest number of seats of any party: 18. It also elected the fewest number of deputies since 2003. The PSDB—to which Neves belongs—saw an increase of 11 seats. Since it takes at least 308 votes out of the total 513 representatives to pass constitutional amendments, the next president will need to build coalitions to push through major legislation. "The fact that Congress has become even more fragmented as a result of these elections means that the practical barriers to implement any kind of reforms after the election are going to become even more difficult," Capital Economics Chief Emerging Markets Economist Neil Shearing told Reuters. Plus, the lower house will include nearly 40 percent first-time deputies, making it the biggest lower house shake-up since 1998.

The Chamber of Deputies also saw another change: a small rise in female representatives. During Sunday’s election, 51 women were elected to the Chamber of Deputies and will make up 9.94 percent of the lower house, compared to 8.77 percent currently.

In the Senate—which renewed a third of the total 81 seats—the PMDB won 19 seats, more than any other party. The PT won 12 seats, the second-largest number. The Brazilian Socialist Party—the ticket the presidential candidate Marina Silva ran on—gained three new seats.