Honduras One Year Later: The Costs of a Coup

Honduras One Year Later: The Costs of a Coup

With June 28 marking the anniversary of the overthrow of Honduran leader Manuel Zelaya, Honduras continues to pay an economic price for the political fallout.

A year after the Honduran military unceremoniously forced then-President Manuel Zelaya out of the country—and office—in his pajamas, the Central American country continues to feel the effects of what was internationally condemned as a coup. Zelaya’s ouster, sparked by his attempts to push through a controversial constitutional referendum linked to presidential reelection, set off months of negotiations and theatrics that fell short of restoring the leader. A November presidential election came and went, with Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo winning the vote by a wide margin to replace the de facto head of state Roberto Micheletti. Still, the Honduran government has failed to win recognition from several Latin American countries, remains left out in the cold by the Organization of American States, and has drawn criticism for human rights issues that include multiple violent attacks on the press. As Honduras marks a dark anniversary, it’s clear the coup’s political fallout has carried an economic price.

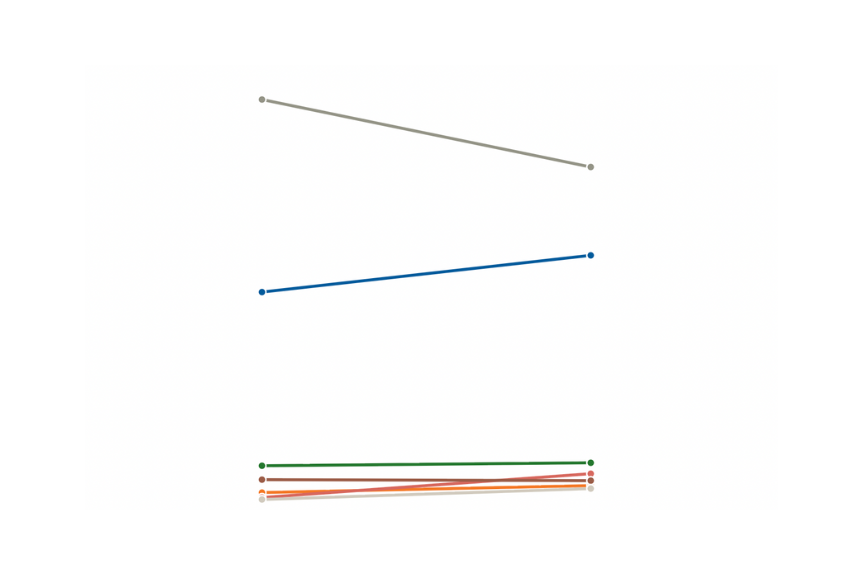

Unemployment stands as a top indicator of Honduras’ economic woes. In 2009, the percentage of Hondurans who were unemployed or underemployed ran at 36 percent, up from 27 percent the prior two years. The Honduran Economists College reports that job creation stands as a major hurdle. The organization says the political crisis led to the loss of 200,000 jobs and forecasts a recovery of just 70,000 positions this year. Moreover, the International Monetary Fund indicates that Honduras finds itself challenged by anemic growth, with the economy contracting by 1.9 percent last year. Although GDP growth of 2 percent is forecasted for 2010, that rate places it among the bottom tier in Latin America, with only El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Venezuela faring worse. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to Honduras also fell, with the Central Bank noting that both the global economic crisis and the coup played a role in a drop from just over $900 million worth of FDI in 2008 compared to almost $500 million last year. The Bank predicts recovery, still below 2008 levels, at $795 million this year.

Honduras also faces soaring food prices due to scarcity exacerbated by tropical storm Agatha, which struck Central America last month. The country’s agricultural ministry reported that prices on some food staples rose by 200 percent since last month, with costs outstripping minimum wages. Corresponding efforts to raise the minimum wage have fallen flat.

Despite ongoing concerns stemming from political instability, Honduras has been able to mend some fences. The World Bank, which froze lending after the coup, resumed development aid in February when it restored $270 million in loans and unveiled plans for an additional $120 million in credit. In March, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced during a press conference in Costa Rica that Washington would restore suspended aid to Honduras, saying: “[W]e think that Honduras has taken important and necessary steps that deserve the recognition and the normalization of relations.” In recent weeks, the United States resumed military aid via an equipment donation, $75 million in USAID projects, and $20 million for security projects folded into the Merida Initiative.

But last year’s ousting of Zelaya continues to bedevil Latin America’s ties with other regions. In May, several countries—including Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela—threatened to boycott an EU-Latin American summit held in Spain because the European Union extended an invitation to Lobo. While the EU praised the country’s November elections, it has been hesitant to recognize the results and urged national reconciliation in Honduras. In the aftermath of the coup, the EU suspended $90 million in aid.

It remains unclear whether Honduras is out of the woods when it comes to future political shake-ups. In recent days, the president and the country’s security minister expressed fears over plots to overthrow the Lobo government. An exiled Zelaya has accused U.S. Southern Command of being part of the plot to overthrow him. Meanwhile, last week 27 members of U.S. Congress penned a letter to Secretary Clinton, urging an assessment of the human rights situation in Honduras as part of a determining factor as to whether to continue providing aid.

Learn more

- AS/COA’s “Timeline of the Honduran Crisis” covers the period leading up to the coup through the November election.

- The AS/COA “Resource Guide to the Crisis in Honduras” includes primary sources following the political crisis.

- Honduran Central Bank’s economic outlook report for 2010-2011.

- June 24, 2010 Letter from 27 U.S. lawmakers to Secretary Hillary Clinton regarding Honduras’ human rights situation.

- IMF 2010 World Economic Outlook includes a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean, including figures on Honduras.

- “A Tough Year for Honduras,” Bloggings by Boz, June 28, 2010.