Explainer: What's the Future of Obama's Executive Action on Immigration?

Explainer: What's the Future of Obama's Executive Action on Immigration?

On July 10, an appeals court heard the case determining the future of the U.S. president’s deportation relief programs.

When U.S. President Barack Obama announced an expansion of his deportation relief programs in November 2014, he offered a chance for millions of undocumented immigrants to seek legal means to remain in the United States. But just three months later, a Texas federal judge issued an injunction and halted the programs before they started. Whether these programs will be implemented remains unclear, although initial readouts from the court's hearing indicate it'll be an uphill battle for the administration. There’s a possibility the programs could begin this summer, but they might also remain in legal limbo until shortly before the 2016 presidential elections.

Where is the case now?

On July 10, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals heard the full case brought by 26 states to halt the two programs—one aimed at parents of U.S. citizens and legal residents, and another expanding an existing initiative for immigrants brought to the United States as children. The two are most commonly known by the acronyms DAPA and DACA, respectively.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) allows immigrants brought to the country before age 16 to get temporary work authorization, allowing them to get a Social Security number and a driver’s license. The status must be renewed every two years. Though the program launched in 2012, the expanded version eliminated an age cap and extended the renewal period to three years. Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) would extend these same benefits to parents of U.S. citizens and green card holders. However, neither program offers a path to legal residency or citizenship.

Previously, on May 26, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals denied the Obama administration’s emergency request to begin the programs. And the U.S. Department of Justice opted not to go straight to the Supreme Court, letting the case continue on its way through the appeals system. While the appeals court could potentially give the green light to the program, it could take weeks or months to announce a decision, said David Leopold, an immigration lawyer and analyst, in an interview with AS/COA Online.

How the appeals court rules will determine the next steps, the National Immigration Law Center explains. It could ban the programs or allow the policy to go ahead. The court could also change the injunction, letting the programs go into effect in the 24 states not involved in the lawsuit.

The crux of the issue

At issue is the president’s ability to change immigration enforcement. Obama created these programs through executive action, using his authority as president to decide deportation priorities. From the outset, critics accused the president of overstepping his legal bounds.

Still, many scholars contend that executive action is constitutional. “It’s up to the president to determine when and to what extent he’s going to enforce federal laws,” said Ilya Somin, a constitutional scholar and a George Mason University law professor, in an interview. “It’s not fundamentally different from the situation where technically, legally speaking, marijuana possession is illegal under federal law for everybody but federal officials virtually never enforce that law on college campuses.”

Not everyone agrees. Elizabeth Price Foley, a constitutional law professor at the Florida International University reflected on the issue in The New York Times’ Room for Debate, saying: “Presidents could simply decide not to enforce entire sections of the Clean Air Act, tax code or labor laws, or exempt entire categories of people—defined unilaterally by the president—on the assertion that those laws are ‘unfair.’”

What comes next?

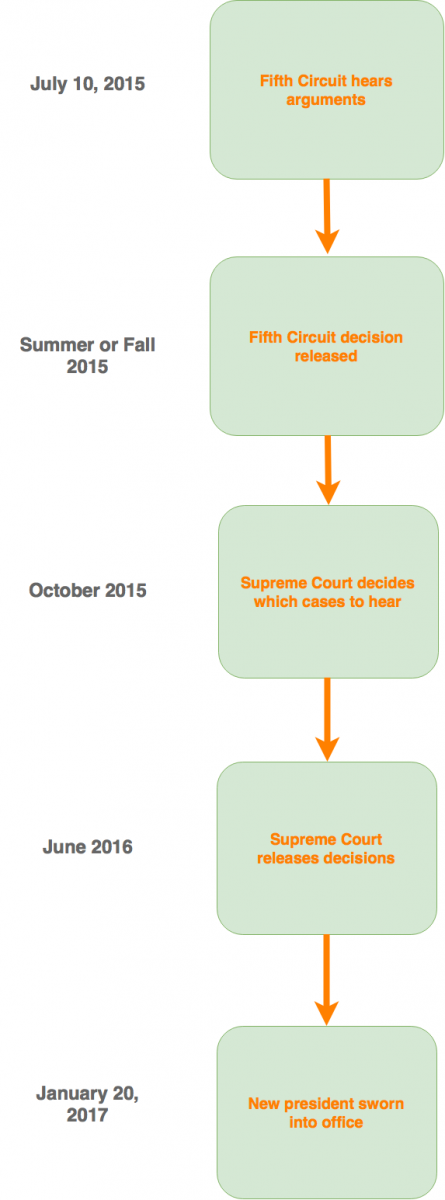

Experts told The New York Times that the loser in the Fifth Circuit will likely appeal to the Supreme Court, which wouldn’t decide which cases to hear until October. The court could also let the eventual Fifth Circuit ruling stand without taking the case. But with two other immigration executive action cases making their way in the appellate courts now, the country’s highest court could be swayed to rule on the issue, said Leopold. If the Supreme Court does hear the case, a ruling may only come in June 2016.

So even if executive action goes into effect, it could be short-lived. The next president might not keep the programs alive, since they depend entirely on the sitting president, Leopold said.

See below for a timeline of key upcoming dates.