Explainer: Chile's 2025 General Elections

Explainer: Chile's 2025 General Elections

In the November 16 first round, will Chileans pick a successor to President Gabriel Boric who will shift the country’s ideological direction?

Since 2006, the Chilean presidency has ping-ponged between left and right; no president has been succeeded by someone from the same political camp and consecutive reelection is banned. So, will leftist President Gabriel Boric will be succeeded by a politician on the right?

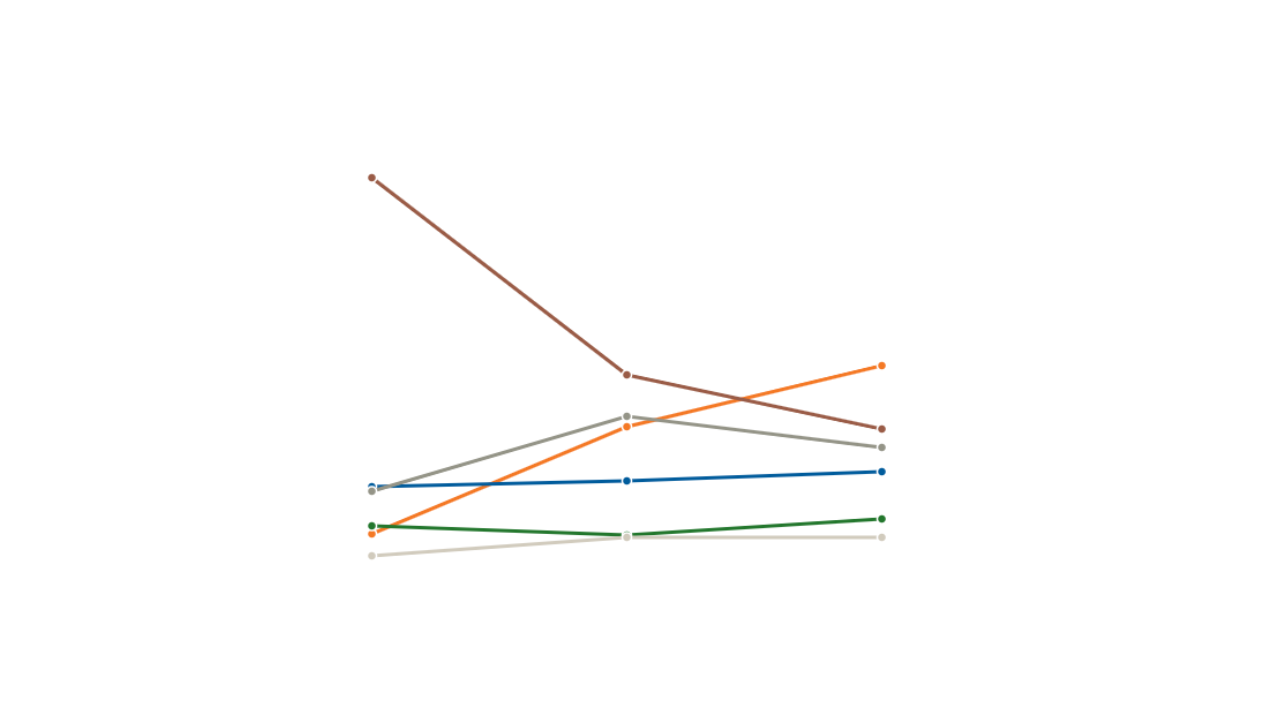

That’s the hope for many of this year’s presidential aspirants. Four right-wing candidates are polling in the double digits, with campaigns that speak to domestic and regional concerns about sluggish economic growth and mounting insecurity. About 48 percent of Chileans believe their country is on the incorrect path. Boric’s approval ratings hover around 40 percent, but a shift away from his progressive politics may be imminent.

Still, to win in the November 16 first round, a candidate needs more than 50 percent of the vote. Polls show no candidate close to that number in part because the Chilean right forwent a primary due to disagreements between major candidates. A December 14 runoff appears likely.

Chileans may not know who their next president will be come November 16, but they will find out the congressional makeup. All 155 members of the Chamber of Deputies and 23 of the 50 seats in the Senate will be elected that day.

What are the major issues Chileans are considering as they head to the polls? Who are the candidates and what are they proposing? AS/COA Online gives a panorama ahead of November 16.

Several prominent right-wing leaders are hoping to turn the ideological tide by succeeding Gabriel Boric. See polling for the November 16 first round.

International lawyer and columnist Paz Zárate discusses the candidates and compulsory voting as the November 16 first round nears.

AS/COA covers 2025's elections in the Americas, from presidential to municipal votes.