Brazil Still Striving to Make the "Great Leap Forward"

Brazil Still Striving to Make the "Great Leap Forward"

Despite significant and sustained efforts by Brazilian officials to raise Brazil's international-trade profile, it seemed all anyone wanted to discuss during recent World Economic Forum meetings in Davos was China and India. This is frustrating for Brazilians, but if recognition in Davos and elsewhere has not been immediately forthcoming, it's because recent efforts have yet to generate the kind of fundamental change in Brazil's economic profile that would cause the world to sit up and take note.

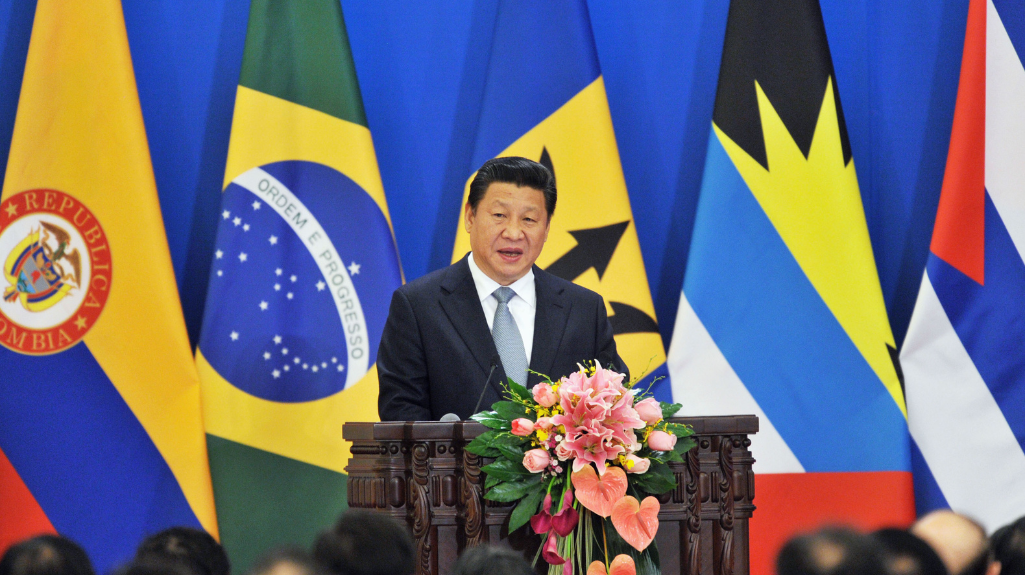

It's not for want of effort. Even as the Brazilian government has been lukewarm to the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas, Brazilian trade officials have been busy developing and consolidating trade relations throughout the world. In the last three years, Brazil's exports to the world have doubled and, more important, through an aggressive effort to open new markets, Brazil's export markets have diversified. While the United States remains Brazil's largest single trading partner, since 2002 trade with the United States grew at a slower rate (146 percent) than with other countries. Brazil has seen its MERCOSUR trade, for example, explode more than 350 percent since 2002. Trade with China and India increased by 250 percent. China is now Brazil's third-largest trade partner.

Like China and India

Similarly, exports to such far-flung places as the Middle East, Russia and Africa grew by two times in just three years. Nonetheless, despite a very public trade offensive, Brazilian trade in 2005 represented less than two percent of global commerce; much of its export growth was driven by traditional agribusiness and primary products. In contrast, for the past generation, Brazil's Asian counterparts have implemented aggressive internal reform measures to ''move up the food chain'' to produce higher value-added goods.

Such experiences are instructive: Brazil's efforts to make a great leap forward to join the likes of China and India will depend as much on internal reforms as on the success of its external trade policy.

While gaining access to Asian, U.S. and European markets remains important, Brazil's greatest challenge is diversifying, not just its export partners but its exports, particularly expanding the production and sale of technology and high-end manufactured products. Last year only half of Brazil's $118 billion exports were manufactured goods, and less than 10 percent of those were high-end technology goods.

Brazilian airplane company Embraer stands as one of the few large-scale manufacturers to make significant in-roads in international markets. Even value- added agriculture faces difficulties, though opportunities to expand the production and export of sugar-based ethanol are hampered by restrictive global-trade policies not of Brazil's making.

Nonetheless, the key to increasing value-added production does not lie solely in trade policy, but also in the macroeconomy. The one-two punch of high interest and tax rates -- among the highest in the world -- have served as a disincentive for investment and growth in Brazil.

Similarly, concerns about intellectual-property protection have dampened the enthusiasm of new investors, while outmoded labor laws make Brazil one of the most expensive countries in the region for companies that seek to increase their efforts in the region.

Perhaps most important, aging and outdated infrastructure is a straitjacket on the Brazilian economy. Brazil has the same 30,000 kilometers of railroads as in 1938, when rubber and coffee exports drove economic activity. To add insult to injury, Brazilian roads have deteriorated to the extent that last year the government declared a state of emergency in the transportation sector.

Most favored nation

In reality, the next few years will be the true test of Brazil's trade ambitions. If the country is to move beyond trade spokesman to trade leader, the government and private sector working together will need to focus on more than gaining larger markets abroad; they will need to change the terms of trade by addressing the most pressing economic issues facing their nation.

The good news is, Brazilian officials know this. And if they are able to address these matters effectively, before long, Brazilians, too, will join the ranks of Davos' most favored nations.

Chris Sabatini is senior director for policy and Michele Valadão Levy is senior director for programs at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas.