Bolivia's Radical Decentralization

Bolivia's Radical Decentralization

President Evo Morales is transferring more authority to departments—even when the results have been politically uncomfortable.

Bolivia under President Evo Morales is undergoing revolutionary change. Since it assumed power in 2006, much of the international attention on the Morales government has focused on its socioeconomic policies. But those policies may ultimately leave less of a political imprint than the transformation of the country’s governing structures. In fact, the most profoundly radical development is Bolivia’s transition from a traditional unitary state toward something resembling a federalized one—though the end point of this process remains uncertain.

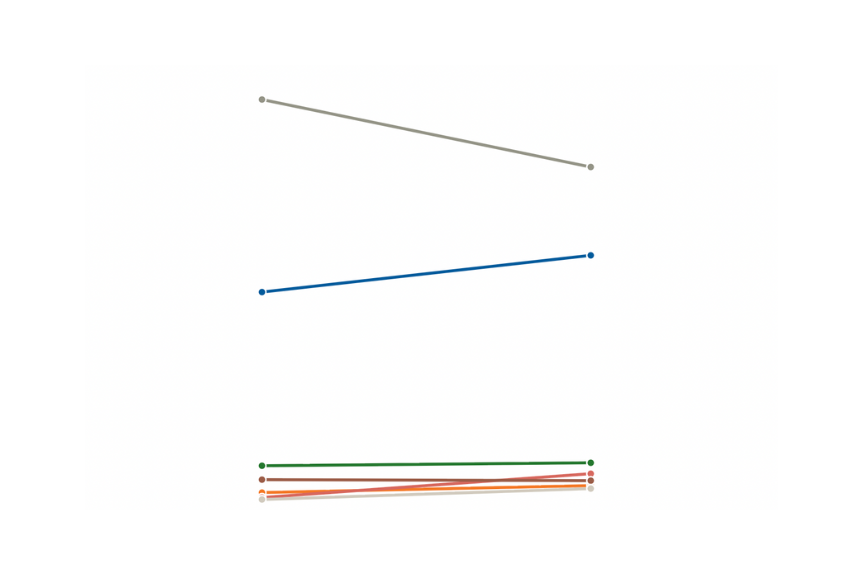

Political power in Bolivia, as in much of Latin America, has been historically centralized in the national government. Subnational authorities traditionally served as agents of the executive. But during the wave of decentralization that accompanied the region’s return to democracy, Bolivia began to move toward the federal models of Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela. With this year’s local and regional elections, it has become the most decentralized of Latin America’s nonfederal states.

It is now worth asking whether the results have advanced Bolivia’s democratic development or hindered it.

The movement toward a federalized structure began in the mid-1990s, when the Ley de Participación Popular (Popular Participation Law) created 311 popularly elected municipal governments (since expanded to 337) and constitutionally guaranteed them direct fiscal transfers. It also included mechanisms for grassroots citizen organizations to play direct oversight and planning roles in local government.

At the time, the neoliberal architects of those reforms argued that municipal decentralization was more effective than granting more powers to Bolivia’s nine departments, which would merely reproduce the inefficiencies of the central government. That was a justifiable concern, since each of the departments was politically and economically dominated by its capital city. The decision to create 311 municipal governments—most of which had fewer than 15,000 residents—was a conscious effort to bring local government to marginalized indigenous and rural communities.

One of the most striking results of the law was the empowerment of a new generation of political leaders, such as Evo Morales. But just as significant, municipal decentralization along with electoral reforms that introduced a mixed-member electoral system, accelerated the decline of Bolivia’s traditional party system.

Read the full text of this article at www.AmericasQuarterly.org

Miguel Centellas is an assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Mississippi. His research focuses on the effects of instituional reform on electoral politics in Bolivia.