Summary: 2013 Presidential Elections and Economic Outlook - What's Next for Chile?

Summary: 2013 Presidential Elections and Economic Outlook - What's Next for Chile?

AS/COA's May 2 panel focused on Chile's future as experts discussed the upcoming elections and economic prospects.

Speakers:

- Gregory Elacqua, Director of the Institute of Public Policy at the School of Economics at the Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile

- David Gallagher, Chairman of Asset Chile; Board Member of the Chilean Public Studies Centre (CEP)

- Carl Meacham, Director, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) Americas Program

- Patricio Navia, Master Teacher of Liberal Studies Program, Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, New York University

- Paula Molina, Anchor and Editor at Radio Cooperativa; Nieman Fellow in Harvard 2012 to 2013 (moderator)

Summary

On May 2—a day after the deadline for candidates to register for primaries in Chile—AS/COA hosted a panel of leading experts to discuss Chile’s political and economic outlook in advance of the November 17 presidential elections. The conversation focused on the upcoming elections, the country’s impressive growth indicators, and the dynamic political and social climate. Panelists analyzed the current challenges and opportunities for future political and economic reforms in the coming years.

Chile Today

Paula Molina of Radio Cooperativa opened the conversation by highlighting the development indicators that have made Chile stand out as a model for growth in the region. Chile is currently in the top rankings for international investors and bankers.The country has a recent history of commitment to democracy and enjoys some of the lowest levels of corruption in Latin America, along with low rates of poverty and unemployment. Molina argued, however, that these economic indicators fail to account for the social and political discontent represented by recent student protests. She argued that the popular protests and marches demand urgent attention from the presidential candidates.

Challenges for the Next Administration

Following Molina’s introduction, Carl Meacham from the Center for Strategic & International Studies focused on the social contradictions in Chile. Although students participating in marches have different demands than previous generations, they are still working within the same social stratification as their parents’ generation. The problem facing Chileans, according to Meacham, is not necessarily free education, but rather the lack of social mobility. Meacham noted that there are huge expectations for the upcoming election, but the question will be how the social situation is going to evolve. He believes that the problem is sociocultural, rather than political.

The Government’s Role in Chile’s Future

David Gallagher of Asset Chile and the Chilean Public Studies Centre continued the conversation by focusing on the changing character of Chilean democracy. He argued that the good economic performance is not reflected in the government’s approval rating. According to Gallagher, the “excessively differential” hierarchical class system, which began during President Lagos’ administration, has begun to face a “healthy rebellion” from the Chilean people. They are now fighting for a say in policies that have traditionally been made behind closed doors. Media scandals and electronic media have allowed for freer press, and, according to Gallagher, “we are witnessing a new democratization of the Chilean citizenry”.

In respect to the upcoming elections, unlike Molina and Meacham, Gallagher believes the political candidates can easily sidestep addressing the demands of the student protests because the students’ demands are not shared by the majority of Chileans.

Education Reforms in Chile—Quality over Quantity

Gregory Elacqua of the Institute of Publicy Policy at the Universidad Diego Portales in Chile agreed with Gallagher that the student protests do not reflect the whole of Chile. As an expert on education, he argued that Chile has made substantial progress in primary and secondary education. Citing a recent study, Elacqua claimed that Chile is ranked 2nd out of 49 countries in the rate of annual academic learning at the K through 12 levels, and he attributes the improvements to higher standards of living, increased government investment in education, and incentives to continue studies.

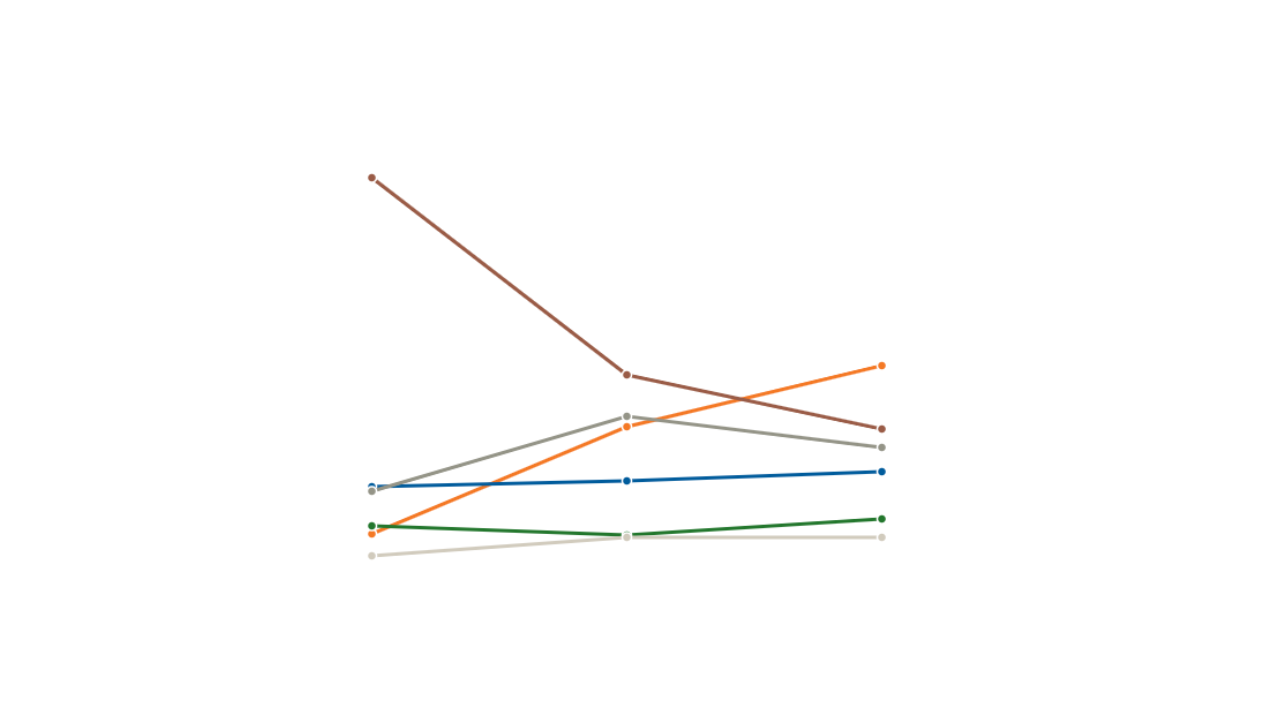

According to Elacqua, in the early 1990s over half the Chilean population lived below the poverty line, with nearly 20 percent living in extreme poverty. Only 14 percent of the population went on to higher education, and the voucher program led to inadequate incentives and unintended consequences. Over the past 15 years, Chile has worked to eradicate extreme poverty and improve education. The annual GDP has increased three-fold, and investment in education has increased four times, now making up approximately 5 percent of GDP. Currently, 90 percent of the population graduates high school, and nearly 50 percent go on to higher education. Notably, the growth has been seen at the bottom, reducing the gap between the wealthy and the poor. The wealthy students have maintained their performance, while the poor have seen the greatest improvement.

Elacqua added a cautionary note: Although there have been gains in quality of education, Chile ranks poorly when it comes to teacher quality. Coupled with the cost of higher education, high debt burden for graduates, and 25 percent dropout rate in the first year of university, there is a sense of urgency to improve the quality of education in Chile. Although student protesters are demanding free higher education, Elacqua believes the low level of preschool education and low female participation are also two major problems that will need to be addressed. For Elacqua, free education is not the answer to all the problems.

Chilean Polls: What They’re Saying about Prospects for the Future

Patricio Navia of NYU’s Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies argued that the formal polls show a very different political and social landscape than the marches and protests we see in the news. The polls show that Chileans are, for the most part, moderate, he said. He believes that any presidential candidate who hopes to win the election in November will need to move to the center.

Navia argued that the student marches and protests are more about inclusion than about political discontent. He claimed that Chileans want to see change, but they want it to be gradual, not radical or dramatic. The polls demonstrate that Chileans value the process of democracy, while also simultaneously rejecting politicians. He argues that their rejection is more one of the political elite class than of politicians themselves. Navia predicts that as the elections draw closer, there will be a race to the center to capture the moderate vote. They will need to make institutions more inclusive through gradual and pragmatic reforms.

Potential Reforms

According to the panelists, the greatest challenges to Chile are the lack of social mobility and the slow progression of social inclusion. They agree that “reform, not revolution, is what Chileans want,” as Navia put it. Rather than focusing on free higher education, they assert that the focus should re-center on providing better quality preschool education, which will reduce the social gap between the wealthy and the poor. Their projection over the next five years includes a tax reform that will encourage redistribution through income tax and social programming. They believe that Chile will continue to have a market-based economy; however, they project that it is likely that there will be more state-led companies in various sectors than private corporations.