Private Hands, Public Lands in Cuba

Private Hands, Public Lands in Cuba

A Cuban reform allows private farmers use of state-controlled land, marking a departure from past policies. Whether the law is far-reaching enough remains to be seen, given that the government retains land ownership.

Since Raúl Castro took over leadership from his brother in late February, Cubans have witnessed a range of modest reforms that range from legal cell phone sales to the right to stay in high-priced hotels that were once reserved for foreigners. Low salaries on the island keep most Cubans from affording such luxuries, prompting critics to label the reforms as “superficial” changes that demonstrate the extent of government control. As U.S. Secretary Commerce Carlos Gutierrez pointed out at COA’s May 2008 Washington Conference, Cubans can buy toasters starting in 2010, but only “because now the government allows you to buy a toaster.”

However, starting last month, Castro approved economic reforms that show signs of a departure from some of the Marxist tenets imposed by brother Fidel. During a June interview in state-run Granma, Minister for Labor and Social Security Carlos Mateu announced an end to the egalitarian salary system in place on the island since 1959. In a country where the average salary stands at roughly $17 a month, the new system would provide incentives for bonuses with the goal of boosting productivity.

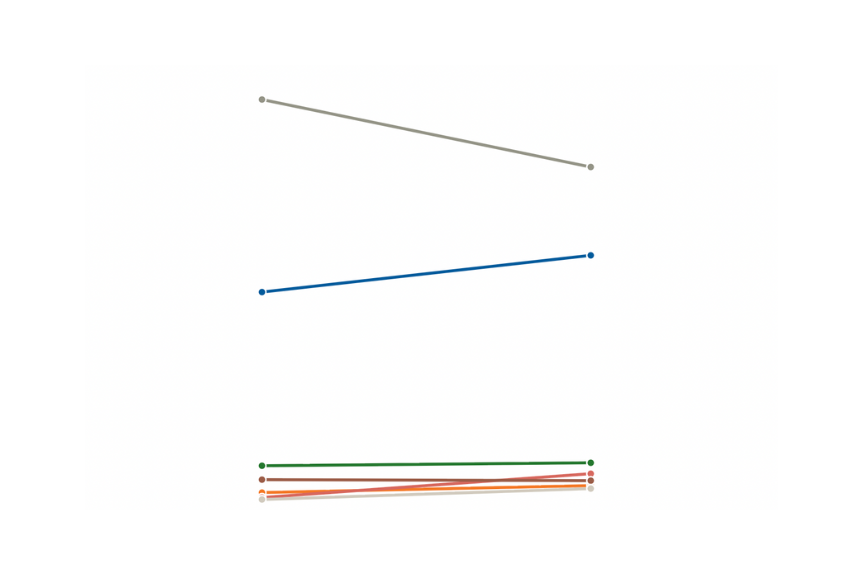

Another change announced July 18 loosens restrictions on private use of public land, reforming the land redistribution laws dating back to 1959—when Fidel Castro took the helm following the Cuban Revolution—that put large swaths of private property into state control. The new laws allow private farmers access to up nearly 100 acres of state-owned land for up to a decade, with the option to renew leases if certain conditions—such as paying taxes—are met. State farms and cooperatives will also gain access to the lands. “This is the first substantial reform to Cuba's economic model carried out by Raul,” Jorge Pinon, a researcher of the University of Miami’s Institute for Cuba and Cuban-American studies, told Bloomberg.

But the extent to which the new land reform could truly spell private property rights for Cubans remains to be seen. As a New York Times article notes, the government, which controls about 90 percent of the Cuban economy, would retain ownership of the land parceled out under the decree. Meanwhile, the reform seeks to address both the rising cost of food imports and the increase in underused farming land—up to 55 percent in 2007.

Some experts have pondered whether Raúl Castro would seek to emulate China’s one-party style of economic liberalization. In that case, Castro may be looking toward a Chinese land reform approved by that country’s National People’s Congress in 2007 that allowed for private property rights. Still, the complicated set of laws gave China’s large peasant population limited opportunity to resell their farms or use their land as collateral on which to borrow and expand their property. As a result, widespread peasant protests—numbering in the tens of thousands across China’s countryside each year--continue to serve as a thorn in the side for Beijing.

Without deeper economic and democratic reform, Cuba’s leaders could find themselves facing similar mounting pressures from the Cuban people. An article by Orlando Gutierrez-Boronat featured in the Spring 2008 issue of Americas Quarterly explores the sense of growing impatience felt by a majority of Cubans frustrated by the slow nature of economic reforms. During U.S. Congressional Testimony, AS/COA’s Senior Policy Director Christopher Sabatini expressed concern that “Cuba remains stuck in the past with little hope or opportunity for change emerging from a tightly controlled, geriatric inner circle.”

Read a program summary and listen to audio of a COA panel discussion “Cuba: What Comes Next?” held after Cuban leader Fidel Castro resigned in March.