Peru Votes: Humala and Fujimori Advance to Second Round

Peru Votes: Humala and Fujimori Advance to Second Round

Nationalist Ollanta Humala won Peru's April 10 election, with conservative Keiko Fujimori taking second place. The two candidates will face each other in a June 5 runoff.

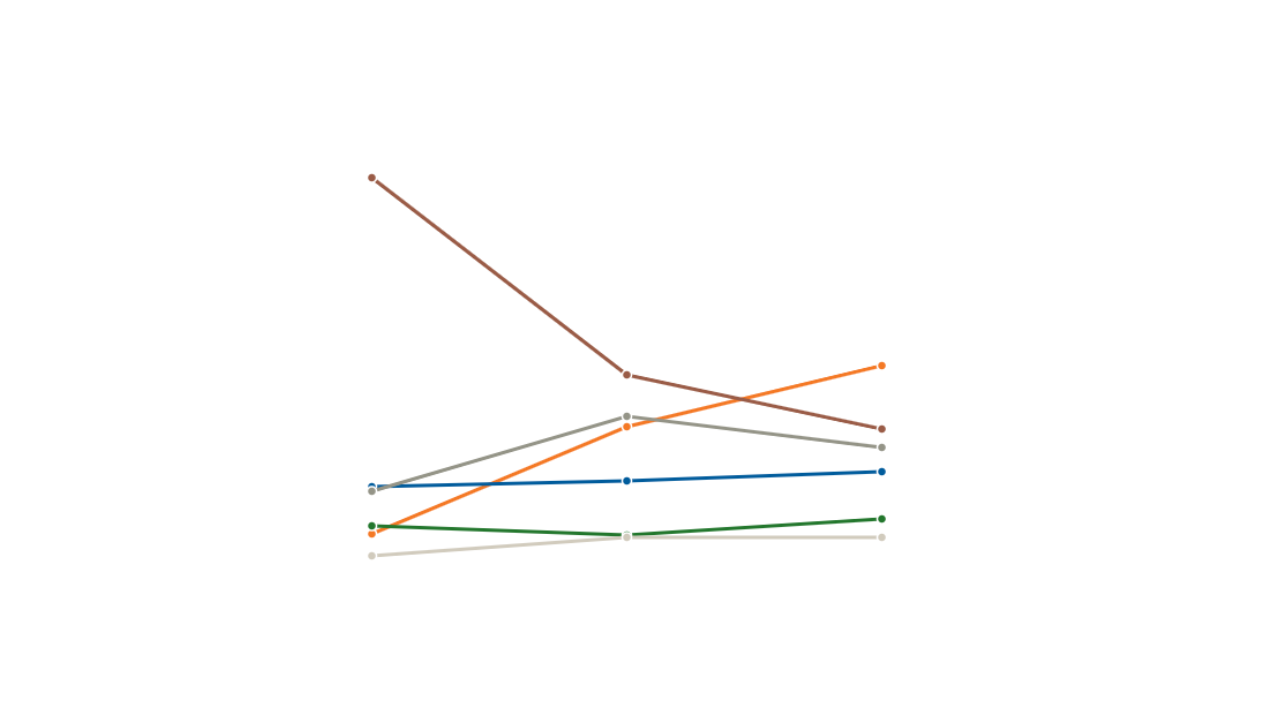

Updated April 11, 2011 - The first round of Peru's presidential election proved what a difference a few weeks can make in a campaign cycle. Nationalist Ollanta Humala won, with 29.88 percent of the vote as of the morning after the election and with 80 percent of ballots counted. He will face conservative Keiko Fujimori, who garnered 23.03 percent of the vote, in the June 5 runoff. Fujimori, in turn, edged out Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, a centrist and former finance minister, who won 20.55 percent. Former President Alejandro Toledo—the frontrunner less than a month ago—earned just over 15 percent of ballots to take the fourth spot, raising questions about how the ground shifted in the election.

Alejandro Toledo’s opening remarks at the presidential debate on April 3 marked the changing tenor of the campaign cycle. “You have to decide not between five candidates,” Toledo said. “But rather between the future of growth and democracy that we represent, and leaping into the abyss.” Former President Toledo, a centrist and an economist by profession, went on to criticize the possibility of scaring away foreign investment and jeopardizing Peru’s enviable economic growth by increasing the role of the state in the economy. Toledo did not name names, but given that four of the five candidates for the April 10 election favored maintaining the country’s free-market model, he clearly aimed his comments at left-wing candidate Ollanta Humala. Last week, polls indicated a major jump for Humala, who had trailed behind Toledo and conservative candidate Keiko Fujimori for most of the campaign. With Humala’s rise, the role of the state in the economy came to dominate the presidential election more than any other issue.

Peru’s business community reacted to the news of Humala’s rise—and win—with nervousness, throwing the country’s currency and financial markets into a tizzy, according to Reuters. Humala has played to the center this campaign, using strategists from Brazil’s Workers Party to cultivate an image comparable to center-left ex-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. But Peru’s business community remembers Humala’s unsuccessful 2006 bid, when he associated himself more closely with Venezuelan firebrand Hugo Chávez. Humala has indicated that he would nationalize the gas industry in the southern part of the country. A greater role for the state in Peru’s economy could bring uncertainty to some $40 million in mining and oil projects planned by the current government.

One of the reasons for Humala’s steady rise is that the political center ran three candidates. Up until a couple of weeks ago, Toledo—who proposes expanding social programs within the context of Peru’s free-market economy—enjoyed a comfortable lead in opinion polls. But he competed directly with former Kuczynski and ex-Mayor of Lima Luis Castañeda, two candidates who espoused a similarly centrist message. Toledo’s popularity declined due to quarreling with the other two centrist candidates, as well as with President García, which analyst Giovanna Peñaflor says exasperated voters.

As Toledo’s lead eroded, leaving more space for Kuczynski and Castañeda, the candidates of the left and right poles of the political spectrum benefited, with Humala attracting support from poorer voters and Fujimori—daughter of ex-President Alberto Fujimori, currently serving a 25-year sentence for human right abuses—with her brand of right-wing populism. The fact that the Peruvian electorate tends not to identify with parties, however, left the country’s elections hard to predict.

It’s not surprising that Peru’s center was divided. The García administration presided over economic growth averaging 7 percent since he was elected in 2006, but his performance as president did not inspire much confidence among Peruvian voters. His approval rating of 27 percent put him among the lowest of Latin American presidents, according to Mexican polling agency Mitofsky. García’s party, APRA, did not run a presidential candidate to replace him. APRA also received a flogging at the polls when it came to congressional elections and will only have four out of 130 parliamentary seats, reports Peruvian daily El Comercio.

García’s chronically low approval ratings may be linked largely to the perception that administration focused on growth without taking measures to redistribute wealth. García did not invest heavily in social programs to alleviate poverty, preferring to put the state’s money into infrastructure projects to drive growth and create jobs. Many Peruvians also feel left out of the commodities boom. That dissatisfaction became apparent two years ago, when indigenous groups in the province of Bagua protested a plan by the García administration issued by decree to open up areas of the Amazon rainforest to oil drilling, logging, and hydroelectric dams. A tense standoff lasting months degenerated into violence in June 2009 and the García administration eventually backed down. Those tensions continue to plague Peru—over 100 communities have organized to protest mining and oil projects, according to the country’s Ombudsman’s Office.

Notwithstanding social conflict, statistics do not paint such a bleak picture. Poverty dropped in Peru from 49 percent in 2004 to 35 percent in 2009, according to The Economist. While income disparity did not decrease significantly, it did not rise. The Economist suggests that one of the factors driving dissatisfaction with the Peruvian economic model could be the rise of conspicuous consumption. The skyscrapers, fancy restaurants, and new shopping malls appearing in Lima and throughout the provincial capitals contrast sharply with the fifth of Peruvians left without access to running water or the fifth of children who are malnourished.

Learn More:

- Read an AS/COA News Analysis about polling in the Peruvian election.

- Get official results from Peru's electoral agency.

- Watch the April 4 presidential debate on YouTube (in nine parts).

- Reuters’ Peru page offers analysis in the run up to the election.

- El Comercio’s election page carries full coverage, including profiles of the candidates and their plans.

- Ipsos Apoyo’s April 3 poll.