Interview: CPJ’s Carlos Lauría on Press Freedoms in Venezuela

Interview: CPJ’s Carlos Lauría on Press Freedoms in Venezuela

AS/COA Online spoke to Carlos Lauría, the senior Americas program coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists about press freedom in Venezuela, how media restrictions affect the presidential campaigns, and violence against journalists.

"Whether Chávez is re-elected or Capriles is elected as president, the challenge will be to restore a climate of tolerance, a climate of dialogue, where all journalists will be able to do their jobs without government interference, harassment, and pressure."

"Whether Chávez is re-elected or Capriles is elected as president, the challenge will be to restore a climate of tolerance, a climate of dialogue, where all journalists will be able to do their jobs without government interference, harassment, and pressure."

Over the course of his term in office, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez has taken steps to undermine the country’s private media outlets, which provide a voice for the critics of the government and offer an alternative to state-run media outlets. Prior to Venezuela’s October 7 presidential election, AS/COA Online’s Nathaniel Parish Flannery spoke to Carlos Lauría, the senior Americas program coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). He discussed some of the steps the Chávez administration has taken to limit press freedoms, how media restrictions affect the presidential campaigns, and violence against journalists.

AS/COA Online: During this year’s election in Venezuela, press freedom is an important issue, but what are specific challenges the country faces around freedom of the press?

Carlos Lauría: It’s very important for the upcoming election. Why? Because an array of legislation, the use of regulatory bodies to target critical outlets and journalists, and systematic government harassment have debilitated the press in a way that has basically diminished its capacity to be able to perform its work in a way that will help Venezuelans access diverse information and make informed decisions. In-depth reporting is needed in this critical moment, in this critical election. Since Chávez took office, several media outlets have been taken off the air. RCTV is probably the clearest example. It was the largest TV network and very critical of the government. That network had been on the air for more than 50 years, but its concession was not renewed because the government decided that they wanted it off the air. It was a political decision. There were several other stations that suffered through a similar process and are now off the air. At the same time, the government created a massive network of state media outlets, which basically transmit propaganda and are used to smear critical journalists who launch verbal assaults against them. All this has created an environment where the media is not able to fulfill its role. Citizens are being deprived of important information. And clearly, it’s affecting the way Venezuelans are receiving information. The government, for example, is not providing statistics on some of the main issues facing Venezuelan this election.

When it comes to the issues that concern Venezuela the most—crime, for example—the government’s not providing information. The government hasn’t provided official statistics on crime since 2004, and has tried to hide this information from the public and from the media. Another example is the prison crisis, which has led to dozens of inmates killed in riots. It’s something of concern for Venezuelans: people, inmates, getting guns and drugs into prisons. All this information, it’s gone unreported.

Prison Minister Iris Valera said in May that they won’t provide any information on the prison riots in El Rodeo, because the media was engaging a campaign to attack the president. Information on inflation, on the economic crisis, about the oil refinery explosion, water contamination: all these issues are critical for Venezuelans facing the election but are going unreported. There’s no in-depth reporting that will allow Venezuelans to make informed decisions.

This problem is probably one of the main challenges for the next administration. Whether Chávez is re-elected or Capriles is elected as president, the challenge will be to restore a climate of tolerance, a climate of dialogue, where all journalists will be able to do their jobs without government interference, harassment, and pressure.

AS/COA Online: In the last few weeks, there have been several attacks on individual journalists. Is this a new development that is specific to the election cycle?

Lauría: It may be related. These most recent instances may be related to election coverage, but there were periods in Venezuela, for example after the coup, when pro-government protests and opposition protests where on multiple occasions journalists were attacked and physically assaulted. This is not new. These latest incidents may be related to the fact that we’re in a period of rising political tensions, but this has happened before in Venezuela.

AS/COA Online: Some watchdog groups have claimed that Chávez has an unfair advantage in the media. How has state-run media impacted this campaign?

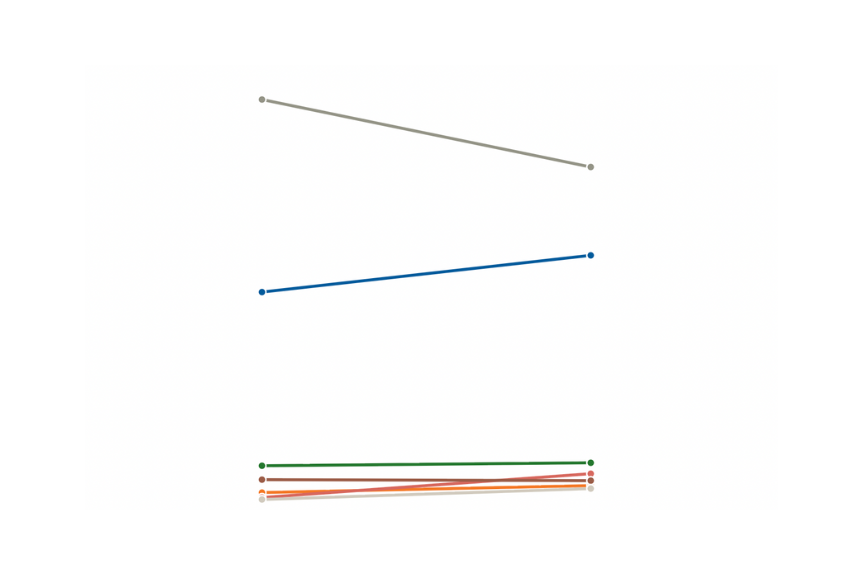

Lauría: The fact that the state has invested heavily in media aimed at discrediting the opposition and critical journalists will probably have an effect. The government knew after the failed coup of April 2002 that in order to challenge the influence of private media, they needed to build a powerful conglomerate that will compete with private media. They’ve been very successful at that. State media allows the president to be omnipresent in the media and gives him the ability to transmit broadcasts simultaneously on all channels, both private- and state-run. He’s had 1,600 hours of TV broadcasts since he took office in 1999.

I think the president has an advantage. There’s only one critical broadcaster remaining in Venezuela; we’re talking about Globovision, a station that goes on the air only in Caracas and the state of Carabobo. This situation allows the government to have a huge presence. I think this may be one of the reasons behind the decision by Capriles to go door to door on these extensive visits and try to be everywhere in order to reach all Venezuelans.

AS/COA Online: Are Chávez’s health issues preventing him from taking full advantage of this state media monopoly?

Lauría: The fact that he’s being less visible in the campaign obviously hurts, but the propaganda is still there. He may not be as present in this campaign, but the propaganda machine is working well and I think it gives him a clear advantage.

AS/COA Online: How does the rise of social media make this election different from previous elections?

Lauría: Social media is allowing many people to use other vehicles of communications. It’s already having an impact. We have documented attacks against journalists, activists, writers who are active on social media. According to Espacio Público, in the last two years, there have been more than 40 attacks against these people.

Emails and Twitter accounts have been hacked. Compromised accounts have been used to transmit messages that favor the government and insult and attack journalists or members of the opposition. There’s a group which has been attributed to some of these attacks called N33. Apparently they have aligned themselves as being pro-government, and have said they’ve been responsible for some of this hacking of websites and Twitter accounts of critical journalists.

AS/COA Online: How does the level of violence against journalists in Venezuela compare to other countries in the region, specifically to Mexico?

Lauría: There’s no level of comparison between Venezuela and Mexico. The problems in Venezuela are completely different from the problems in Mexico. I usually try not to establish comparisons between countries, because even countries that have perennial violence are different from each other because of the political context. So I think there are no parameters to compare what’s going in Venezuela and what’s going on in Mexico.

Mexico has clearly become one of the most dangerous countries for journalists in the world, not only in the Americas. Almost 50 journalists have been killed or disappeared since President Felipe Calderón took office in December 2006.