Electoral Reform: Chile to Implement Gender Quotas

On the verge of its ratification, learn what Chile’s first-ever gender quota law entails.

This month, Chile’s legislature agreed to set its first-ever gender quota as part of an electoral reform that now awaits the Constitutional Court’s approval. The reform, which replaces a binomial voting system set in 1989 with a proportional system, intends to create a more representative government. As one of the provisions aiding more diverse representation, the gender quota will set a minimum and maximum for the presence of both sexes in party candidate lists: both men and women must make up at least 40 percent of candidates, while neither sex can make up more than 60 percent of candidates. First introduced by President Michelle Bachelet in May 2014, the law would be implemented beginning in 2017, and is set to expire after 2029 elections.

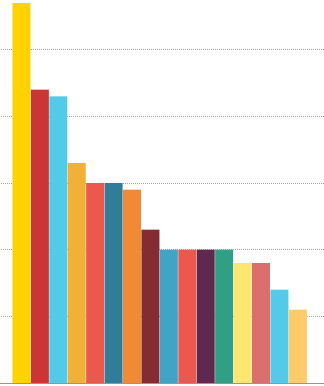

Despite having a woman as president, Chile is among the Latin American countries with the lowest proportions of women in its legislature. Currently, women compose 15.8 percent in both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. This is well below the 25.7 percent average of countries across the Americas, and the 21.8 percent world average. Moreover, the number of women in the Chilean government today is only 5.8 percent more than it was in 1998. At that pace, it could take 40 years to have gender balance in the parliament, according to a study by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Additionally, the reform comes with an economic incentive to attract women candidates and the parties that endorse them. Already, all candidates are reimbursed approximately $1.10 per vote they receive to compensate for campaign costs, whether or not they win. But the new law ups reimbursement for female candidates, in particular, to approximately $1.50 for each vote. On the other hand, parties will receive about $9,739 for each female candidate elected.

For Chilean Secretary of State Claudia Pascual, the reform is less a gender quota than a criterion for gender parity. “It’s not what critics at one point called securing seats for women,” Pascual told La Tercera. “We’re only promoting the participation of women in elections, so they’ll go and also compete with male candidates.”

Members of Chile’s conservative party, the Independent Democratic Union (UDI), are among the reform’s critics. For example, UDI Senator Hernán Larraín claims the quota will restrict primary elections by forcing the inclusion of female candidates even if the primary winners are men.

The majority of Latin American countries currently have gender quota laws, though percentage thresholds vary. With a 40 percent minimum requirement for any given gender on candidate lists, Chile’s quota law is most similar to those of Mexico and Honduras. Before the law, some Chilean parties had adopted voluntary quotas for candidate list, such as the Party for Democracy, the Socialist Party of Chile, and the Christian Democratic Party. However, these are rarely enforced, according to the Quota Project.