Venezuela’s Governing Party Expands Local Influence

Venezuela’s Governing Party Expands Local Influence

The United Socialist Party of Venezuela won the lion’s share of governorships and regional legislature seats in December elections and could deepen the country’s local-level socialist commune system.

As a result of the December 16 state elections, Venezuela’s governing party extended its reach within state governments as officials hope to further expand local party influence. Despite continued uncertainty about President Hugo Chávez’s health, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) succeeded in winning the lion’s share of governorships and regional legislature seats—after electoral rezoning. Some in the opposition worry that this electoral victory could lead to changes in governance, giving more power to locally based and federally funded “socialist communes.”

The PSUV victories come on the heels of nationwide redistricting—the second of its kind in two years. In 2010, the National Electoral Council redrew electoral districts in eight states, some of which happen to be opposition strongholds, prior to the parliamentary elections. The PSUV now has a majority in the National Assembly. In June 2012, the National Electoral Council rezoned the country’s districts for the state elections. Watchdog group Súmate noted that no information was available about how population and geographic distribution factored in to the rezoning. Venezuelan daily El Universal described the redistricting as gerrymandering, since the new electoral zones give an advantage to the party that obtains the largest number of votes—which was the PSUV in both elections. Nevertheless, the PSUV faces mounting campaign costs after observing strong support for the opposition; during October’s presidential election, Chávez defeated Miranda Governor Henrique Capriles by only 11 points. “It seems that increasingly, electoral victories for the government are more and more costly,” political scientist Javier Corrales noted during an AS/COA conference call.

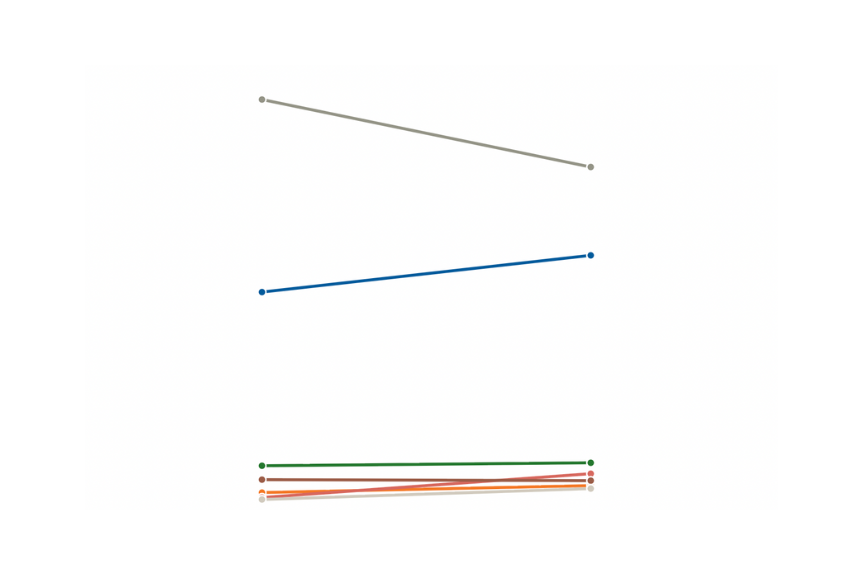

On December 16, the PSUV and allied parties won 20 of 23 governorships. On the Americas Quarterly blog, AS/COA’s Christopher Sabatini noted: “While Capriles’ win in Miranda reinforces his leadership of the opposition, this was clearly a victory at the state level for the chavista PSUV party.” The opposition won in Amazonas, Lara, and Miranda states, but lost five critical governorships that it had won in 2008. Meanwhile, the ruling party and allied candidates won by margins of 13 points or more in a dozen states; in Trujillo, PSUV candidate Henry Rangel won by over 63 points. Rangel was one of several winning PSUV candidates hand-picked by Chávez to run for governorships; others included El Aissami in Aragua state and Chávez’s brother Adán in Barinas. Analyst James Bosworth explains that: “This reward for their loyalty keeps these leaders outside Caracas and serves an added benefit of protecting Vice President Maduro if an internal party fight begins.” Chávez chose the vice president as his successor, though other PSUV leaders harbor presidential ambitions.

The PSUV also snatched up 186 regional legislative spots, making up 78 percent of the 237 elected legislators. Overall, the PSUV won control of 22 out of 23 state legislatures. Of the three states won by opposition governors, only one state—Amazonas—gained opposition control of the regional legislature.

With the ruling party gaining majority control of state legislatures, some observers say lawmakers could take steps toward expanding the federal government’s commune system. Passed in December 2010, the Communes Law gave power to these so-called comunas socialistas (socialist communes), local bodies who carry out social programs, infrastructure projects, and other services funded by the federal government. The PSUV could go further, pushing to change the laws to adopt a “communal state,” taking power away from state legislatures. Opposition members are against the communes, saying they transfer power from governors and mayors to the central government. By some estimates, the government created up to 500 communes, though ABC España reported in November that 90 percent of those had failed in their economic activities due to corruption. Next year, funding for the communes will increase by 37 percent from $1.7 billion to $2.27 billion.

While some fear deepened commune system could erode local governments, others say it could take a long time to implement, and replacing locally run government services like health clinics and policing would be a complex process. In addition, the goals are lofty: the federal government aims to build 500 comunas socialistas per year so that by 2019, 70 percent of the population lives under the commune system. But the expansion of communes is a long time coming, former Venezuelan Foreign Relations Minister Armando Durán told El Nuevo Herald. “Fourteen years ago, a process of change began in the structure of the state, of power, of society, of the economy. This is a process that has not stopped,” he said.

In other Andean news:

- The UN-led conference on agrarian reform in Colombia kicked off on December 17 as part of the country’s peace talks process. Approximately 1,200 rural workers and leaders from business, government, and non-profits participated in the three-day meeting that forms part of negotiations with the FARC guerrilla group.

- In an interview with Ecuador’s El Comercio, Mexican historian Enrique Krauze discusses prospects for Latin American leadership in the potential absence of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, given his poor health. He explained what would happen to Chávez’s “Bolivarian project,” saying it would become “Brazilianized” under an open economic model with social programs. “This is also the model in Peru, which is in Latin America’s best interest,” he said.

- This week, Bolivia and Brazil agreed on additional measures to further anti-trafficking operations, including installation of Brazilian radars on the tri-country border with Peru and coca leaf testing to more efficiently track the origin of narcotics. Both countries are also in the final phase of negotiating Brazilian drone operations to monitor coca plantations in Bolivia.