Explainer: Colombia's 2018 Legislative Elections

Explainer: Colombia's 2018 Legislative Elections

The March 11 vote—the first in the FARC post-conflict era—will have significant implications for the May presidential vote.

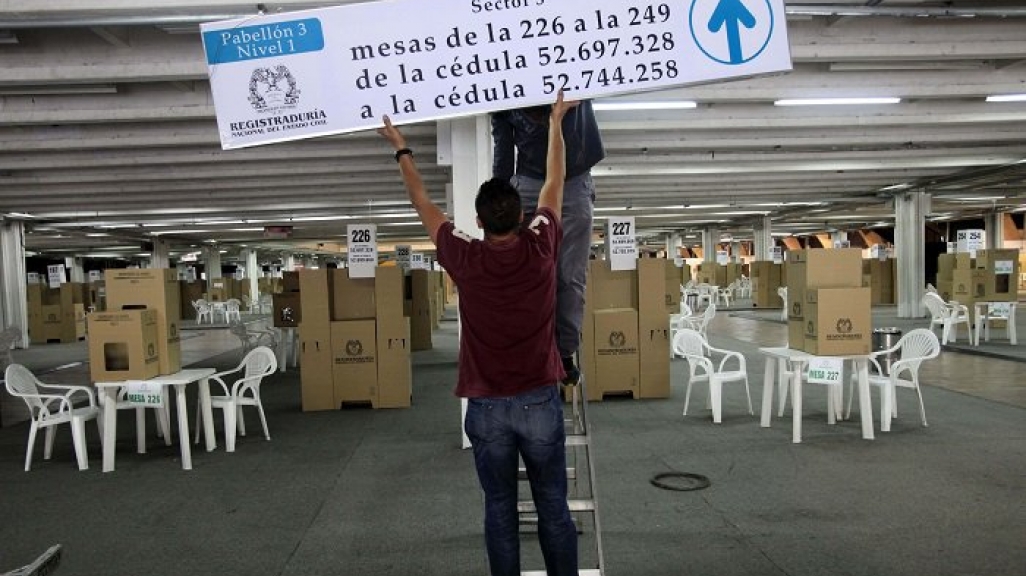

On March 11, Colombians head to the polls to vote in legislative elections for 102 Senate and 166 House of Representatives seats. It’ll be the first national vote in the FARC post-conflict era, and the next Congress will include at least 10 members from the demobilized guerrillas’ political party.

Colombian legislative elections are determined via proportional representation, with parties winning seats in Congress based on the share of votes they receive. One hundred of the Senate seats are voted on nationally, while 161 House of Representative seats are elected per the 32 departments and one capital district. Additionally, Colombia’s Afro-descendant and indigenous communities elect two senators and four representatives via a separate ballot, and the expat community gets one congressperson in the lower chamber. Experts estimate the threshold of votes a party needs to get in order to secure any representation in Congress, starting with representatives in the House, will be around 390,000 votes this year.

The FARC will automatically receive five seats in both chambers in the two upcoming legislatures, with candidates determined by the party, per the terms of the peace agreement signed with President Juan Manuel Santos. Additionally, another new rule grants the presidential runner-up a Senate seat, while his or her running mate will get a seat in the House. The new measures will bring the total number of legislators up to 108 senators and 172 representatives for the 2018–2022 session.

More than 36 million Colombians are eligible to vote on Sunday. Voting is not mandatory in Colombia, and turnout in the legislative elections four years ago was 44.6 percent, which was more or less in line with historic results. While voters in the country will vote on March 11, Colombian expats have the week of March 5 to 11 to cast their ballots. More than 720,000 expats are registered to vote this year, up 33 percent from the last elections in 2014, compared to national voter rolls which are up just 6 percent.

Polling is famously unreliable in Colombia, so much so that independent news site La Silla Vacía decided after the 2014 elections to no longer include voter intention surveys in their election coverage. In the October 2016 plebiscite on the FARC peace deal, polls overestimated the “Yes” vote’s position by an average of more than 30 points; the “No” side ended up winning by less than one half of 1 percent.

That said, if a 7,000-voter survey from late February is any indication, the Democratic Center is heading into Sunday’s voting in the strongest position, while the Party of the U and the Conservative Party are on the verge of losing the lion’s share of their congressional seats. Party of the U—created by then-Minister Santos to support Álvaro Uribe’s 2006 presidential reelection bid—won the largest number of seats in 2006 and 2010. But after Santos won the presidency in 2010, he and Uribe diverged sharply over the FARC peace process. Uribe founded the Democratic Center party, which debuted in the 2014 elections by taking the second-highest number of seats in Congress, including a Senate seat for Uribe, a vantage point from which he’s helmed the opposition since. In perhaps the most telling show of how much Santos and the Party of the U’s clout has slipped, the party currently is fielding no candidate for president in 2018.

Santos is unpopular, and his signature achievement—2016’s peace agreement with the FARC—is in a precarious stage of implementation. State presence in former FARC-controlled rural areas is weak: Almost 300 community and indigenous leaders have been murdered in the last 26 months, according to the Colombian Public Defender’s Office. Other illegal armed groups—including National Liberation Army (known as the ELN) members, dissident FARC who did not disarm, neo-paramilitaries, and drug traffickers—still operate in much of the territory, including in Colombia’s national parks.

Uribe, while popular, is facing charges in 28 cases before the country’s Supreme Court. Many of those cases are tied to his alleged responsibility in the false-positives story that marred his presidency (2002–2010) and other killings that took place during his time in office.

After completing their formal disarmament in August 2017, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia kept its FARC acronym and rebranded as the Revolutionary Alternative Common Force political party. Though watching former guerrillas participate in the political process has been a divisive issue, the stated goal of the peace process was to convert what was an illegal political armed rebellion into a disarmed, legal one. The party will not field a presidential candidate in 2018, however, after former leader and would-be candidate Rodrigo “Timochenko” Londoño Echeverri had to pull out for health reasons on March 8 and the party declined to field a replacement.

Iván Duque leads Gustavo Petro by up to 20 points in four polls ahead of the June 17 runoff.

Colombia is different from the rest of the region in that it holds its legislative general elections on a separate day than presidential ones during the same electoral year. As such, the legislative vote plays an important role in the presidential race by first showing whose parties will hold the most power in Congress and also by giving a preview of which candidates are the most viable at a national level.

Along with voting for senators and representatives, Colombians also have the opportunity to vote in two of what are called “interparty consultations.” In what functions essentially as an open primary, there will be one ballot where voters will choose which of three right-wing candidates—the Democratic Center’s Iván Duque, the Conservative Party’s Marta Lucía Ramírez Blanco, or former Inspector General Alejandro Ordoñez—should be the nominee for the conservative coalition. The race between Duque, Uribe’s heir apparent for the Democratic Center bid, and Ramírez, who came in third in the 2014 race on the Conservative Party ticket, will be closely watched. Then there’s also the possibility that left-leaning voters will cast votes for Ramírez or Ordoñez just to thwart Uribe and Duque.

A second ballot between leftists Gustavo Petro and Carlos Caicedo (both of whom head first-time coalitions) is less competitive, with Petro, a former Bogotá mayor and congressman, as the clear favorite.That said, people will be keeping an eye on the total number of votes he receives as an indication of how viable he can be nationally. Though he left the mayor’s office with 61 percent disapproval, Petro has proven to be a shrewd campaigner over the last year and managed to stay on message and in the news. He travels to Washington this week to meet with OAS and IACHR officials to denounce recent threats on his life.

A host of candidates hovering around the middle of the political spectrum, including former Medellín Mayor Sergio Fajardo and ex-Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras, will not be on any ballot this Sunday.

The presidential general election is May 27, with an all-but-a-given runoff scheduled for June 17.