Explainer: What Are the BRICS?

Explainer: What Are the BRICS?

Find out how this group of five markets evolved from an investment catchphrase to a bloc aiming to boost its collective global clout.

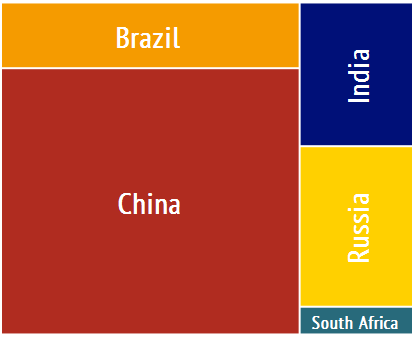

Updated July 16, 2014—Originally an investment catchphrase, a group of five countries known as the BRICS decided to band together on the global stage. The BRICS, made up of Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa, are characterized by rapidly growing economies and increasing international influence. With over 40 percent of the world’s population, these countries’ combined output constitutes more than 20 percent of global GDP. Economists predict that Brazil, China, India, and Russia will join the United States as the five largest economies in the world by 2050.

Leaders from the BRICS have taken steps to capitalize on the group’s economic potential by holding summits to discuss market integration and diplomatic cooperation. On July 15, the heads of state of all five BRICS countries convened in Fortaleza, Brazil, for their sixth summit, cementing the creation of a new development bank and a foreign exchange reserves pool.

AS/COA Online looks at how BRICS has changed over the years and where the group is heading.

|

See how BRICS trade has evolved in a series of infographics. |

Origins and Evolution

The BRIC acronym originally referred to the informal grouping of Brazil, China, India, and Russia. Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill first coined the name in 2001, predicting that the four countries’ share of global GDP would increase significantly over the first decade of the century and would outpace growth of some of the world’s largest economies.

Over the next few years, foreign ministers from these four countries began to meet sporadically, first convening in 2006 during the sixty-first UN General Assembly in New York. These dialogues looked at ways the countries could cooperate politically.

Soon, though, talks turned to the economic crisis. As the 2008 recession hit U.S. and European markets, steady growth in China and India increased the BRIC countries’ confidence in weathering the slowdown. Oliver Stuenkel, a fellow at the Berlin-based Global Public Policy Institute, wrote that the instability in developed countries juxtaposed with the relative strength of developing economies “caused a legitimacy crisis of the international financial order, which led to equally unprecedented cooperation between emerging powers.”

This cooperation came to light when BRIC finance ministers met in November 2008 in São Paulo, Brazil and released a communiqué detailing their commitment to work together in light of the financial crisis. That month, then Russian President Dmitry Medvedev and his Brazilian counterpart Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva agreed to arrange the first BRIC heads-of-state summit.

The countries approved a rotating presidency, which is given to the country that hosts the annual summit. As such, Brazil will assume the position this month. When China held the presidency in 2010, BRIC became BRICS when former Chinese President Hu Jintao wrote a formal invitation to South Africa to include the country in the group.

Heads-of-State Summits

The first heads-of-state BRIC meeting took place in June 2009 in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Medvedev described the summit as a necessary reaction to the global financial crisis. During the meeting, leaders discussed the importance of creating a more diverse international monetary system, with a diminished reliance on the dollar as the global reserve currency.

The second summit was held the following year in Brazil, and saw the addition of South African President Jacob Zuma as an attendee. Topics included Iran’s nuclear program and the importance of cooperation in the areas of energy and food security.

In December 2010, South Africa was officially invited to become the fifth member of the group. The sub-Saharan African country had actively campaigned for an invitation and saw its inclusion in the group as a way to connect the BRIC economies with the African market. BRIC formally became BRICS at the third summit in Hainan, China in April 2011.

In April 2012, the fourth summit was held in New Delhi, India, where heads of state called for expanded voting rights at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The delegates also began considering an alternative BRICS-led development bank, a proposal that was formally agreed to at the fifth summit in South Africa in March 2013.

Also during the South Africa summit, countries agreed to establish the BRICS Business Council made up of five entrepreneurs from each country to discuss ways to expand cooperation. The Council has a rotating chair between the five countries.

In July 2014, the sixth summit took place in Fortaleza, Brazil, where leaders signed agreements to establish a development bank and a currency reserve pool. Discussions also touched on the IMF’s lack of reforms to ensure greater representation of developing countries, as well as sustainable development.

BRICS Institutions

The BRICS model has evolved from investment lingo to a formalized network hoping to capitalize on the group’s collective promise in the wake of instability in the global economy. In doing so, it has taken on a greater geopolitical role, with aims to enact institutional reforms that shift global power. While initial discussions focused on the need to reform international institutions, including the IMF and the UN Security Council, recent developments center on creating a new institutional body. At the BRICS presidential summit in 2013, delegates agreed to establish a BRICS development bank which would serve as an alternative to the World Bank.

|

Watch a video to find out what experts think about the bloc's future. |

Leaders formalized this institution at the July 2014 summit, signing an agreement to create the “New Development Bank” with $100 billion in capital. Initially, the five countries will each underwrite $10 billion in capital for a total of $50 billion. Located in Shanghai, the bank will fund infrastructure and sustainable development projects in both BRICS countries and developing markets. The first bank president will hail from India, and the presidency will rotate. The board of directors will come from Brazil, and the first chair of the board of governors will be Russian. South Africa will be home to the bank’s first regional center for Africa. The heads of state instructed finance ministers from the five counties to work on organizing the bank’s operations. Slated to open in 2016, bank membership will be open to other countries, though BRICS capital share cannot fall below 55 percent.

Heads of state also signed an accord to found a joint foreign exchange reserves pool called a Contingent Reserve Arrangement—similar to the IMF—which establishes an initial reserve of $100 billion and acts as an emergency option for BRICS countries with balance-of-payment troubles. Much of the fund will be provided by China, which will contribute $41 billion. Brazil, India, and Russia, will each contribute $18 billion while South Africa will contribute $5 billion. "It is a sign of the times, which demand reform of the IMF," said Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff at the summit.

Adding New Members

Before the July summit, there was speculation about the possible invitation of Argentina to the BRICS. For the first time, Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has been invited to attend the summit as the only non-bloc head of state in attendance. The invitation came during a May 28 meeting between Russia and Argentina’s foreign ministers, and fueled discussion of the country's possible inclusion in the BRICS membership, given the process of South Africa’s incorporation in 2011. But during the summit, Rousseff said Argentine membership was not in the cards, though she said it could happen in the future with consensus among all five members.

Incorporating new countries has proved controversial. O’Neill himself expressed doubt over the merit of South Africa’s addition, claiming that other countries with high growth, including South Korea, more adequately fit the description of a BRIC as he laid out in his 2001 paper. The Economist even suggested that South Africa’s inclusion took place to represent African countries in a way that kept the acronym intact and not as a result of comparative economic factors.

Plus, adding new members raises questions over both the permanence and efficacy of the label. Numerous countries, including Indonesia, Mexico, and Vietnam, fit the emerging market description as Argentina does, some economists say. For example, Indonesia, which has the second fastest economic growth in Asia after China, has for years lead economists to ask if BRICS should instead be BRIICS.

Rachel Glickhouse contributed to this report.