The Best Thing Manuel Noriega Ever Did for Panama Was to Lose Power

The Best Thing Manuel Noriega Ever Did for Panama Was to Lose Power

After the dictator’s passing, U.S.-Panama relations went from hostility to development spurred by open trade, writes AS/COA’s Eric Farnsworth for The Washington Post.

On Dec. 20, 1989, President George H.W. Bush sent 27,000 troops to Panama to topple the dictatorship of self-declared “Maximum Leader,” Manuel Noriega. The invasion — code-named “Operation Just Cause” — killed 23 U.S. personnel and several hundred Panamanians in the name of protecting U.S. citizens and interests as well as restoring Panama’s path to democracy.

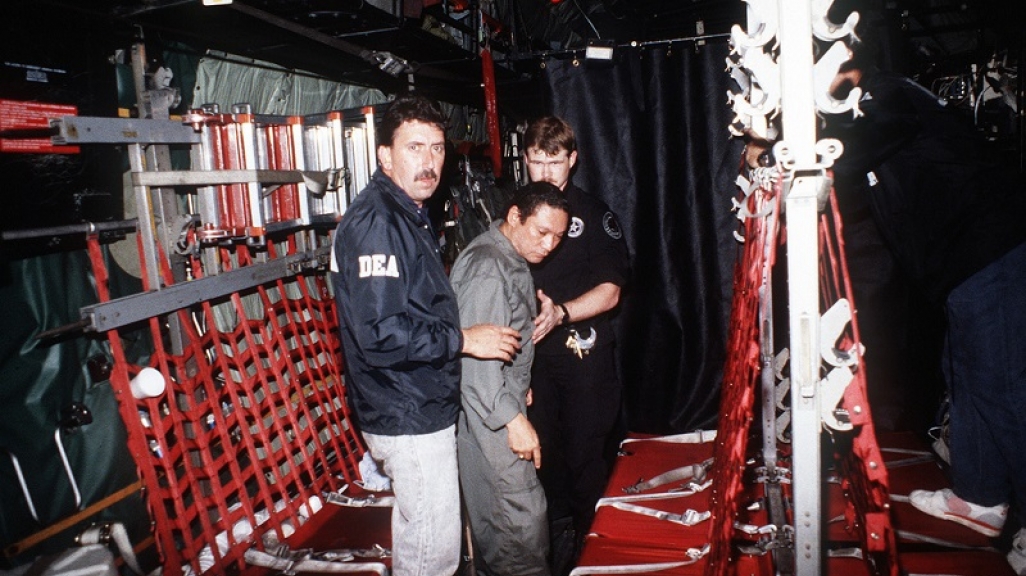

By the time of the invasion, Noriega, whose security forces had killed a U.S. service member, had become a menace to military and civilian personnel. He actively facilitated the trafficking of illegal narcotic drugs; threatened the orderly, treaty-mandated transfer of the Panama Canal to the United States; and overturned the democratic process as he brutalized his own citizens, including opposition political leaders. He surrendered on Jan. 3, 1990, several days after fleeing and hiding in the papal nunciature, where U.S. military and Drug Enforcement Administration agents blasted high-volume rock music (which Noriega reportedly hated) to get him to depart the protection of the Vatican.

This was, perhaps, the last time many Americans thought about Noriega — or even Panama — until his death Monday at age 83. After the invasion, Noriega, who was once a key source of intel for the United States, was convicted and sentenced to prison — first by the United States, then France and then Panama. He remained out of sight for much of the time until he died — forgotten, even though his actions had provoked the largest U.S. military action to that point since Vietnam.

Still, Noriega’s absence changed Panama’s national trajectory dramatically. Prior to his imprisonment, the United States was understandably reluctant to relinquish the Panama Canal — a crown jewel of global engineering and commerce — to an indicted dictator. But once democracy was restored, the United States recommitted to turning the canal over to Panama and returning full sovereignty over the Canal Zone by 2000. Both governments redoubled their efforts, and the orderly, effective turnover of the canal was achieved on schedule.

The government of Panama has subsequently opened a larger third set of locks to handle increased cargo as a means to optimize the canal as an artery of global commerce and directly assist Panama’s efforts to take full advantage of its geographic position in the global economy. Today, Panama’s professional stewardship of the canal is widely recognized, providing a model for other governments in managing state-owned infrastructure projects and enterprises for the public good.

Symbolism abounds. In one generation — literally — the United States and Panama went from hostility and military action to development spurred by globalization and open trade. Panama — under the leadership of Martin Torrijos, whose father, Omar Torrijos, negotiated the treaties that gave Panama control of the canal — agreed to a regional free-trade agreement with George W. Bush, son of the president who invaded the country in part to protect the canal.

Panama moved from dictatorship to democracy. The United States moved from overlord to partner. Panama’s dollar-based economy has since boomed, although the release of the Panama Papers has somewhat tainted economic success with allegations of corruption.

It is hard to imagine a similar course for Panama had Noriega remained in power. His efforts to erode and effectively dismantle democratic institutions, had they gone on for much longer, could easily have turned Panama into a one-party dictatorship and cult of personality, using the proceeds from the canal as a personal piggy bank to fuel politically motivated spending and massive corruption without transparency or a commitment to the public good. It offers a cautionary reminder of what Panama’s alternative course could have been if its corrupt, drug-trafficking dictator had continued to rule.

This article was originally published in The Washington Post.